A Blue Revolution?

Seawater desalination, the industrial production of drinking water from the ocean, is a practice of increasingly intense interest to thirsty cities across the globe. And why not? It promises the ability to provide a reliable water source that is (seemingly) invulnerable to climate change. What is more, the market is responding, with a global estimated value of roughly $18 billion[1] (c.f., Swyngedouw and Williams 2016). And there is significant expected growth, up to $32 billion (that’s about half the estimated size of the wind industry),[2] in the next four years.

These trends have gained attention across a range of sectors and funders. For instance, the World Bank is enthusiastic:

Today, over 20,000 desalination plants in more than 150 countries supply about 300 million people with freshwater every day.reshwater every day. Initially a niche product for energy rich and water scarce cities, particularly in the Middle East, the continued decrease in cost and environmental viability of desalination has the potential to significantly expand its use – particularly for rapidly growing water scarce coastal cities.[3]

All of this has occurred amidst discussions of a “Green New Deal” (O’Neill and Schneider 2021). But, the notion au courant in the water sector is “the blue economy” (Bond 2019). For example, the European Union’s Blue Economy Report outlines the need for desalination’s proliferation, because it is “poised to provide a solution to this impending crisis,” i.e. climate change (emphasis added).[4] And so, while the wind turbine has now become the symbol of the “green economy”, desalination is becoming a similarly captivating “blue” bastion. Yet, it’s important to ask: to what extent does desalination present a “revolution” that responds to calls for a socio-ecological transition technology?

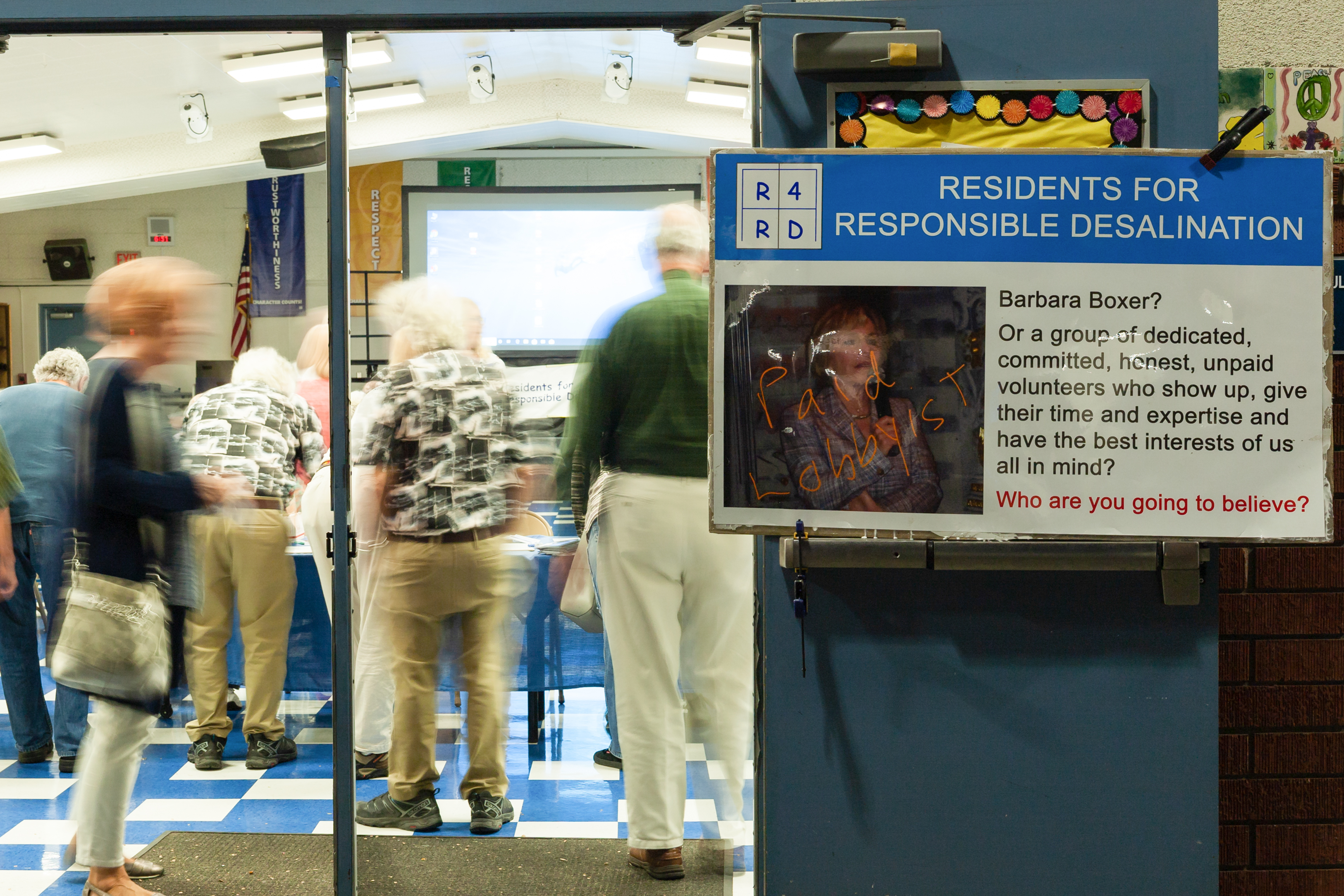

During a prior research project on the water politics of the American Southwest, my interest in desalination was sparked when I noticed stark differences between public opinion data compared with what I was reading in the news and hearing from informants.[5] For example, the Pacific Institute Statewide Survey: Californians and the Environment, asks “do you support or oppose building desalination plants along the California coast?” The question has not been posed consistently; however, the data provides a useful indication. In 2006, 56% supported the idea. By 2017, that number was up to 67%, and in 2021, 68% were in favor.[6] And yet, a quick search of news stories indicates opposition among the communities into which desalination projects have been, or potentially will be, built. As I discovered in the course of my ethnographic research, there may be reasons to be skeptical of desalination as the source of an ecological, modern future for coastal regions. And, this case also opens up important questions about the possibilities for collective action, perceptions of risk and uncertainty, and the political economy of climate change adaptation more generally.

Climate change adaptation is generally defined as any initiative that aims to reduce risks associated with climate change (Shi and Moser 2021). These risks include droughts, heat waves, flooding as the result of sea level rise, and more (Sovacool, Linnér, and Goodsite 2015). However, as more adaptation strategies are implemented, scholars have been concerned that these efforts are not always pursued for their vitally necessary aspects, i.e., as a means of saving society from climate catastrophe, but rather with varying degrees of explicit or implicit emphasis on financial benefits. More directly, the private sector is looking to cash in on the climate crisis (Jerneck 2017; Keucheyan 2018). Some examples of this include carbon markets (Knox-Hayes 2013), tax-increment financing (Baker et al. 2016), catastrophe bonds (Johnson 2014), and a miscellany of public-private partnership financing models for industrial infrastructure (Hodge and Greve 2019). The implications of this “climate financialization” has been varied, from promoting gentrification, to furthering environmental injustices, and dispossessing civil society of democratic processes.

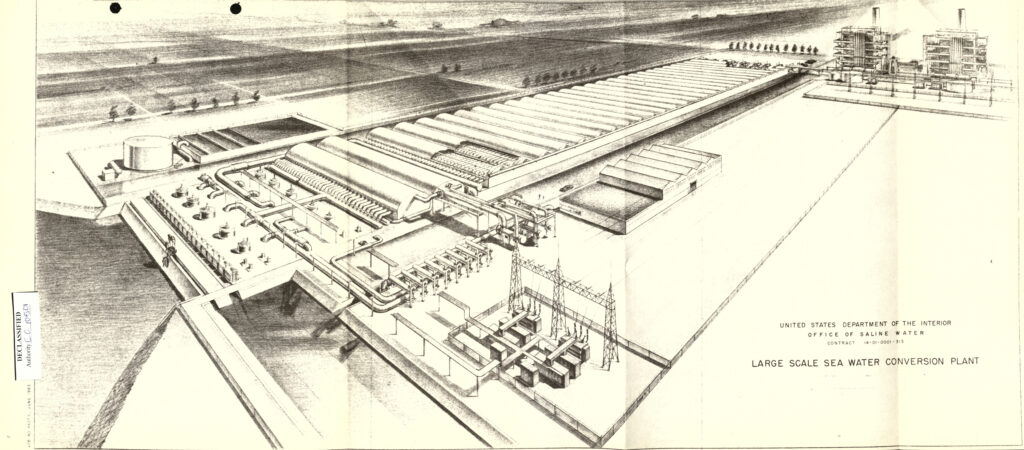

As I have argued elsewhere, the birth of desalination began in the Cold War, during which time it had strong technopolitical tendencies. As such, it was not a climate adaptation policy, per se. Desalination was part of the active utilization of technological development to further political goals. Seawater conversion, as it was often referred to in the documents, reports, and correspondence I analyzed from the Office of Saline Water (OSW) archives, was a widely circulated idea among elite global policy networks, with the endeavor likened to ambitious space programs (O’Neill 2020: 327-8). For example, on September 16, 1960, OSW Director A.L. Miller expressed his agenda with an emphasis on scientific progress in areas like osmotic membrane science:

To maintain our position as the world’s greatest nation, we must place greater emphasis on basic research for scientific knowledge—the most challenging and exciting frontier we have ever tried to conquer. Our ability to compete in world markets in the coming decades will be determined by the research and development we are willing to support today in order to penetrate the ever-expanding frontiers of science. [7]

However, by 1972, the OSW was absorbed into other departments like the Office of Water Resources Research. For a time, it seemed that the hopes for low-cost potable ocean water that could be produced at scale were dashed.

Today, the link between notions of prosperity and technological innovation are being reinvented. While desalination was once a technopolitical archetype, I want to suggest that it is quickly becoming a symbol of uncertainty.

Developing a Sociological Approach to Understanding the Politics of Desalination

California is in the midst of an aggressive push for desalination (Williams 2018; Poupeau et al. 2019). Governor Gavin Newsom[8] supports the practice, as did his predecessor, Jerry Brown. Since the early 2000s, there have been numerous drought relief bills[9] and proposed plans for plants to quench the state’s thirst.[10] As such, desalination marks a new moment in California’s ever-present “water wars,” which are now taking on highly politicized dimensions (Scoville 2019). Due to the fact that desalination plants are some of the most expensive infrastructure projects ($1 billion), governments are unwilling and indeed, unable, to pursue them alone. As one expert told me succinctly: it’s “a lot of money and a lot of risk” (Interview with Executive Director of a public Southern California water agency, June 2020). But risk for whom and what kind?

Critical geographers Alex Loftus and Hug March (2016) have argued that, from the perspective of industry and government, desalination constitutes a shining example of ecological modernization, because profit making can be mixed with supposedly “green,” or in this case blue, innovation. As formulated by sociologists Gert Spaargaren and Arthur Mol (1992), this would mean that desalination is a solution that posits that within capitalism, we can transition out of the present phase of society as “dirty and ugly industrial caterpillar,” and towards society as “ecological butterfly” (see also Huber 1985: 20). Of course, it remains too early to tell if the proverbial butterfly will emerge, but what I found in my research is that the conceptualization/perception of risk is important to the way desalination, both as an idea, and in terms of its material reality, interacts with society and social groups.

I am not alone in trying to grasp the implications of desalination – the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) argues that we should pause to consider its implications:

“The unintended negative consequences of adaptation that can sometimes occur are known as ‘maladaptation’. Maladaptation can be seen if a particular adaptation option has negative consequences for some…or if an adaptation intervention in the present has trade-offs in the future (e.g., desalination plants may improve water availability in the present but have large energy demands over time).”

(de Coninck et al. 2018: np, emphasis added).

While this is a good start, we also need to consider social implications. On this front, it is useful to consider the theory of sociologist Ulrich Beck (e.g., 1992). One of Beck’s primary concerns was the proliferation of societal risks and their responses. The implications of these risks are a restructuring of social relations via measurement, projection, and the contestation of interlocking technological and social risks. The consequences then become extended contexts of of fear, mistrust, and uncertainty in society.

I have already noted a certain disconnect between lived reality and public opinion with desalination, but similar trends are emerging in the “renewables sector,” broadly conceived. For example, if we look at the surveys conducted by political scientists Barry Rabe, Christopher Borick, and colleagues in the National Surveys on Energy and the Environment, we see strong support (as high as 62%) for wind and solar subsidies.[11] However, it is routinely a different story on the ground (Hirsh and Sovacool 2013).

What’s going on? In his recent work on wind energy, environmental sociologist Shaun A. Golding identifies a key problematic. As our society of proliferating risk and contestation forges ahead, we increasingly observe a societal devolution into fear, suspicion, and uncertainty at the hands of technologies that are supposed to improve our condition. However, Golding argues, people are not always ready to raise their awareness to the level of what sociologist C. Wright Mills (1959) called the sociological imagination (formulating one’s personal troubles in the context of public problems). Instead, supposed climate adaptation technologies are what Golding calls “beacons of uncertainty.” Rather than solving our problems or helping people to see their collective malaise, they may actually be drowning out “threats associated with global climate change and ecological degradation, making them appear as abstract possibilities in a distant tidal wave of other possibilities” (2021: 73). This point was brought home during an interview I conducted with a long-time professional hydrogeologist and public official who had been around the desalination debates for more than two decades. For him, a concern about the availability of water should not automatically mean there is a need for the production of new water. For him, water budgeting, conservation, reuse, and recycling are much better places to begin. Furthermore, when local public water agencies work on these solutions, he was concerned that it has been harmful to the public. In his view, by introducing desalination into the adaptation equation, you also introduce confusion and uncertainty:

you’re going to confuse and upset people that we have this project that we are working on [a previous water recycling infrastructure project], and you’re going to have a competing project (the desalination plant)? Just go away!…We’ve been wasting our time, and their money and time, and the board’s time, because nobody wants to buy this very expensive water!

(Hydrogeologist and water expert – Interview, September 2019).

Furthermore, desalination is not done just anywhere – it is specific in its requirements of land, energy, and other resources, and as the case of the United States is showing, a conducive political and regulatory climate. During fieldwork, my aggrieved interlocutors saw a contradiction in the siting of numerous industrial waste, energy, and oil projects in their midst – an area they called “the toxic triangle” (O’Neill 2021). As one resident put it to me, the area of coastline and neighborhood where the plant I studied would be sited has become “a good dumping ground” utilized to improve the municipal tax base (Interview, March 2020). And indeed, who wants to live near a cacophony of industry? However, I want to pick up on Golding’s articulation about the politics of climate adaptation here. The formulation of the desalination issue was hardly ever a structural critique as I observed it. Rather, it often manifested as a personal trouble. As one local resident explained to me, he often uses just such a framing to entice people to come to townhalls and be more engaged:

I’ll put on my capitalist hat whenever I can when I want to be able to communicate with my neighbors in a way that they will listen to me. The capitalist hat says your property values, your hotel incomes, your parking meters, your craft beer, are propped up on the cleanliness of the environment.

(Interview March 2020, emphasis added).

It is tremendously difficult to step outside of certain ingrained forms of instrumental rationality (Gunderson, Stuart, and Petersen 2018; Gunderson 2015, 2016). And while I am sure many of us will be sympathetic to the tact of economistic thinking – and probably have used it ourselves – this likely unconscious atomization of the “trouble” needs to be problematized if we want to think more seriously about climate change adaptation. Such statements beg for sociological analysis because they conceive of risk as quite divorced from humanity. Instead of talking about people’s lives, we are implored to discussions of property values, hotels, parking lots, and the like. Similarly, we need to think in ways that are not just preventative, like so many technological fixes, i.e., staving off the problem until a new technology can be innovated (O’Neill and Boyer 2020), but generative and restorative with regard to our relationship to the natural world (Abrahamsen and Williams 2009; Harvey 2020). We need to apprehend how, in an important way, understanding risk in terms of property, even if one is attempting to oppose industrial development, is to think about the future according to a logic of capitalism. When we think of risk this way, we are not, in effect, thinking about the riskiness of people not having water to drink, but we are thinking about revenue streams, asset classes, rents, and taxes, which are all categories that are precisely incorporated and calculated within things like financial models. Even if it is well-meaning, it is a fundamentally human-decentered analysis.

Desalination and the broader discussions emerging about the blue economy offer important insights to consider for future research, activists and practitioners. For instance, sociologist Ryan Gunderson, alongside Diana Stuart and Brian Peterson have discussed similar issues with regard to space travel by drawing on Mark Fisher’s concept of capitalist realism (a termination of thinking about, let alone working to find solutions toward, alternatives to capitalism) (Fisher 2009). Indeed, if we understand climate change adaptation in its broadest sense as any initiative that aims to reduce risks that have been associated with climate change, why could the colonization of Mars and the abandonment of the planet not make the list? Instead, what is needed is a discussion about climate adaptation strategies that addresses how they fit within the wider forces and structures of capital accumulation and nature appropriation (Moore 2015). This needs to happen in a systematic way across a variety of topics, from desalination to wind, outer space and more, despite recent new green dealings (Luke 2009) to pave the way for a just, equitable future. And yet at the same time, we need to continue to work towards uncovering the meanings, positions, and motivations behind the strategies of climate adaptation if we will be able to address their discourses. This is consequential because at their core they too often rely on the maintenance of already existing financial, technological, and political arrangements. And hopefully, we will see how few of the innovations that are being sold to the public are actually as new as we are led to believe.

Notes

[1] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-desalination-market-report-2021-market-was-valued-at-17-7-billion-in-2020-and-is-expected-to-frow-with-a-staggering-cagr-of-9-51-from-2020-to-2027–301264141.html

[2] https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/01/29/1976640/0/en/Water-Desalination-Market-to-grow-at-a-CAGR-of-9-5-to-hit-32-billion-by-2025-Global-Industry-Analysis-by-Growth-Factors-Value-Chain-New-Technologies-Cost-breakdown-Investments-Oppo.html

[3] https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31416. This remains a hotly debated topic within academic and industry circles, as research supported by the United Nations, for example, has shown that the actual discharge of brine, the hyper-saline byproduct of desalination is higher than predicted. See Jones et al. (2019).

[4] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/676bbd4a-7dd9-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1

[5] https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2022/02/22/a-parched-west-remains-divided-on-desalinating-seawater

[6] https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/ppic-statewide-survey-californians-and-the-environment-july-2021.pdf

[7] RG380 Office of Saline Water – Office of the Assistant Secretary for Water pollution Control/Office of Saline Water –Entry # A1 4: Statements of Director Arthur L. Miller 1960-1966. This statement is taken from Page 6 of his September 16th address before the Armed Forces Chemical Association’s 15th Annual Meeting at the Sheraton Parks Hotel in Washington D.C.

[8] https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2021-02-23/newsom-pushes-poseidon-seawater-desalination

[9] https://www.gov.ca.gov/2021/05/10/governor-newsom-announces-5-1-billion-package-for-water-infrastructure-and-drought-response-as-part-of-100-billion-california-comeback-plan/

[10] https://water.ca.gov/-/media/DWR-Website/Web-Pages/Programs/California-Water-Plan/Docs/RMS/2016/09_Desalination_July2016.pdf

[11] https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/studies/36368

References

Abrahamsen, Rita and Michael C. Williams. 2009. “Security beyond the State: Global Security Assemblages in International Politics.” International Political Sociology 3(1): 1-17.

Baker, Tom, Ian R. Cook, Eugene McCann, Cristina Temenos and Kevin Ward. 2016. “Policies on the Move: The Transatlantic Travels of Tax Increment Financing.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106(2): 459-469.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk society: Towards a New Modernity. New York, NY: Sage.

Bond, Patrick. 2019. “Blue Economy Threats, Contradictions and Resistances seen from South Africa.” Journal of Political Ecology 26(1): 341-362.

de Coninck, H., A. Revi, M. Babiker, P. Bertoldi, M. Buckeridge, A. Cartwright, W. Dong, J. Ford, S. Fuss, J.-C. Hourcade, D. Ley, R. Mechler, P. Newman, A. Revokatova, S. Schultz, L. Steg and T. Sugiyama. 2018. “Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response.” In Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson- Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-4/

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is there no Alternative? Winchester, UK: John Hunt Publishing.

Golding, Shaun A. 2021. Electric Mountains: Climate, Power, and Justice in an Energy Transition. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Gunderson, Ryan, Diana Stuart and Brian Petersen. 2018. “Ideological Obstacles to Effective Climate Policy: The Greening of Markets, Technology, and Growth.” Capital & Class 42(1): 133-160.

Gunderson, Ryan. 2015. “Environmental Sociology and the Frankfurt School 1: Reason and Capital.” Environmental Sociology 1(3): 224-235.

Gunderson, Ryan. 2016. “Environmental Sociology and the Frankfurt School 2: Ideology, Techno-science, Reconciliation.” Environmental Sociology 2(1): 64-76.

Harvey, David. 2020. The Anti-capitalist Chronicles. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Hirsh, Richard F. and Benjamin K. Sovacool. 2013. “Wind Turbines and Invisible Technology: Unarticulated Reasons for Local Opposition to Wind Energy.” Technology and Culture 54(4): 705-734.

Hodge, Graeme A., and Carsten Greve. 2019. The Logic of Public–Private Partnerships. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Huber, Joseph. 1985. Die Regenbogengesellschaft. Ökologie und Sozialpolitik (The Rainbow Society. Ecology and Social Policy). Frankfurt am Main: Fisher.

Jerneck, Max. 2017. “Financialization Impedes Climate Change Mitigation: Evidence from the Early American Solar Industry.” Science advances 3 (3): e1601861.

Johnson, Leigh. 2014. “Geographies of Securitized Catastrophe Risk and the Implications of Climate Change.” Economic Geography 90(2): 155-185.

Jones, Edward, Manzoor Qadir, Michelle TH van Vliet, Vladimir Smakhtin and Seong-mu Kang. 2019. “The State of Desalination and Brine Production: A Global Outlook.” Science of the Total Environment 657: 1343-1356.

Keucheyan, Razmig. 2018. “Insuring Climate Change: New Risks and the Financialization of Nature.” Development and Change 49(2): 484-501.

Knox-Hayes, Janelle. 2013. “The Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Value in Financialization: Analysis of the Infrastructure of Carbon Markets.” Geoforum 50: 117-128.

Loftus, Alex, and Hug March. 2016. “Financializing desalination: Rethinking the Returns of Big Infrastructure.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40(1): 46-61.

Luke, Timothy W. 2009. “A Green New Deal: Why Green, How New, and What is the Deal?.” Critical Policy Studies 3(1): 14-28

Mills, C. Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Moore, Jason. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. Verso Books, 2015.

O’Neill Brian F. 2020. “The World Ecology of Desalination: From Cold War Positioning to Financialization in the Capitalocene.” Journal of World-Systems Research 26(2): 318-49.

O’Neill, Brian F. 2021. Water for Whom? Desalination, Financialization, and the Cooptation of the Environmental Justice Frame. Unpublished manuscript, Presented as part of the Environmental Sociology section of the American Sociology Association roundtable sessions. August 10, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

O’Neill, Brian F. and M.J. Schneider. 2021. “Fracking, Public Health, and Biden’s Green New Deal.” The Society Pages. https://thesocietypages.org/specials/fracking-public-health-and-bidens-green-new-deal/

O’Neill, Brian F., and Anne-Lise Boyer. 2020. “Water Conservation in Desert Cities: From the Socioecological Fix to Gestures of Endurance.” Ambiente & Sociedade 23: e00691.

Poupeau Franck, Brian F. O’Neill, Joan Cortinas-Muñoz, Murielle Coeurdray, and Eliza Benites-Gambirazio 2019. The Field of Water Policy: Power and Scarcity in the American Southwest. New York, NY: Routledge.

Scoville, C. 2019. “Hydraulic Society and a ‘Stupid Little Fish’: Toward a Historical Ontology of endangerment.” Theory and Society 48(1): 1-37.

Shi, Linda., & Susanne Moser. 2021. Transformative Climate Adaptation in the United States: Trends and Prospects. Science. 372(6549: eabc8054.

Sovacool, Benjamin K., Björn-Ola Linnér, and Michael E. Goodsite. 2015. “The political economy of climate adaptation.” Nature Climate Change 5(7): 616-618.

Spaargaren, Gert, and Arthur PJ Mol. 1992. “Sociology, Environment, and Modernity: Ecological Modernization as a Theory of Social Change.” Society & Natural Resources 5(4): 323-344.

Swyngedouw, Erik and Joe Williams. 2016. From Spain’s Hydro-deadlock to the Desalination Fix, Water International, 41(1): 54-73.

Williams, Joe. 2018. “Assembling the Water Factory: Seawater Desalination and the Techno-politics of Water Privatisation in the San Diego–Tijuana Metropolitan Region.” Geoforum 93: 32-39.

Brian F. O’Neill is a doctoral candidate and research fellow at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in the Department of Sociology. Working at the nexus of environmental sociology and political economy, his research focuses on environmental politics, justice, and the financialization of industrial practices related to climate change adaptation. His work has appeared in venues such as the Journal of World-Systems Research, International Sociology, Berkeley Journal of Sociology, Natural Areas Journal, Journal of Political Ecology, and Visual Studies. More information about his work can be found at https://www.brianfoneill.net.