A line of ants walking throughout a 5-liter white plastic recipient, wrapped in black trash bags and trespassed by roots, was my first experience with a landmine. This artifact enmeshed into nature and co-produced a toxic wilderness.

Landmined landscapes are spaces transformed by war: where life continues, adapting to trash, metals, plastic, and explosives.

Improvised antipersonnel landmines are a cheap, lethal, handmade artifact composed of local scrap and adapted to every environment. In highly biodiverse areas, landmines are as diverse as ecosystems. FARC guerrilla groups in Colombia re-assembled plastic bottles of soda, syringes, nails, motorbike chains, and home-made explosive to fabricate these artisanal weapons. The effectiveness of these low-cost weapons relies on the co-production of landmined landscapes: they are sensitive, tailor-made traps perfectly designed to deceive (Duica-Amaya, 2020, 2021). These particular landscapes are socioenvironmental technologies connecting multiple artifacts to co-produce weaponized natures.

Conservation as the collateral effect of war is not a novel subject. “Rogue infrastructure” (Kim, 2016a: 173) armored the 38th parallel border between North and South Korea, converting the DMZ into a conservation hotspot that was later declared a biosphere reserve by UNESCO (Denyer, 2019; Duffy, 2014; Marijnen et al., 2020). The lethality of landmines in Zimbabwe made the bush especially dangerous for poachers, resulting in the protection of endangered species like elephants from poaching, but leaving them vulnerable to landmines at the same time (Hallagan, 1981, p. 536; Gaynor et al., 2019). It is estimated that more than 90% of armed conflicts in the second half of the twenty-first century have taken place in highly biodiverse areas (Hanson et al., 2009). We are witnessing a deep co-production (Jasanoff, 2004) of new natures as a result of war in these landmined landscapes: an “anthropocene of war,” as Brauch and Scheffran (2012) have called it.

Landmines are an emblematic guerrilla weapon whose main purpose is to maim and not to kill. We recall, for example, images of the Vietnam war where the Viet Cong used these artifacts to ambush and demoralize US soldiers. FARC guerrilla groups learned directly from these examples and others to adapt this artisanal technology to the Colombian landscape (Duica-Amaya & Moreno-Martínez, 2022). The technology consisted not only of the improvised explosive artifacts (IEDs) themselves, but, more importantly, on ecologically-cunning ways of adapting these weapons to every landscape.

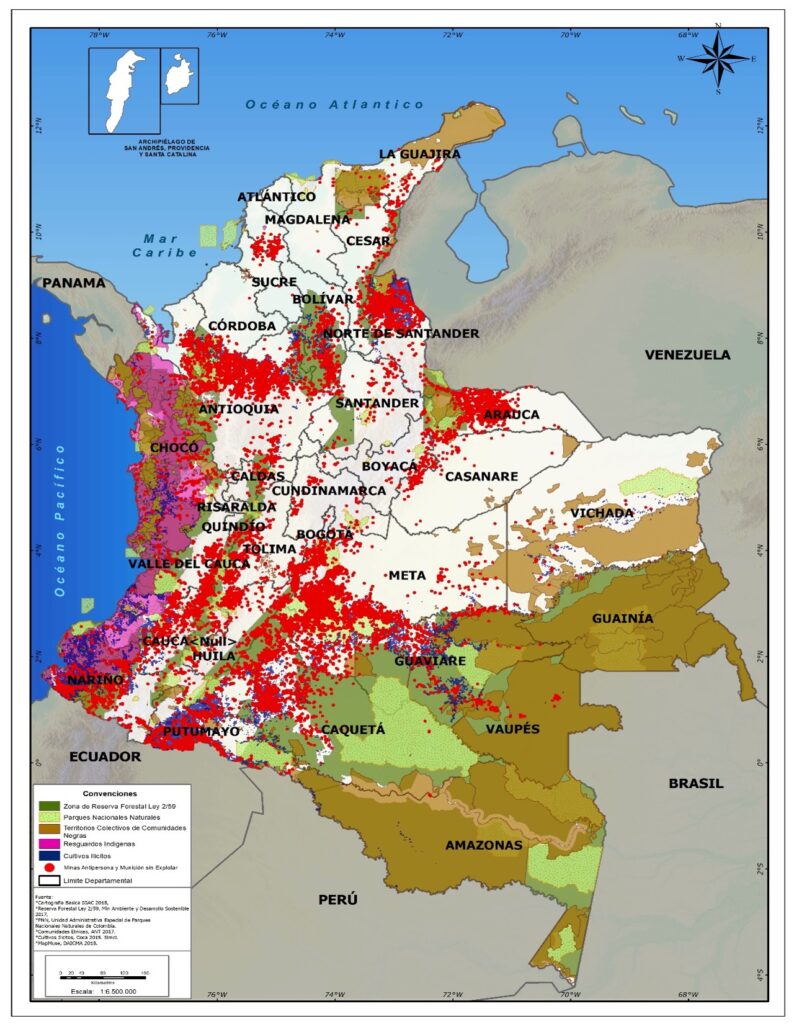

Landmine warfare is a technological system highly effective for hybridizing every artifact into the environment. Landmines today are enmeshed into trees and roots, embracing stones in the water and cohabitating with ants, bears, cows, dogs, cajuches and other animals, depending on the particular ecosystem. Landmined landscapes in the Amazon overlayed the hotspots of biodiversity in natural parks, forest reservation areas, and territories of indigenous communities.

Landmine contamination refers not only to the threat of stepping on these artifacts (even when the warring parties have demobilized), but also to the deforestation that results from their removal. Hence, “demining” requires not only taking out the mines but deactivating all the environmental and cultural war-technological systems where these artifacts were installed.

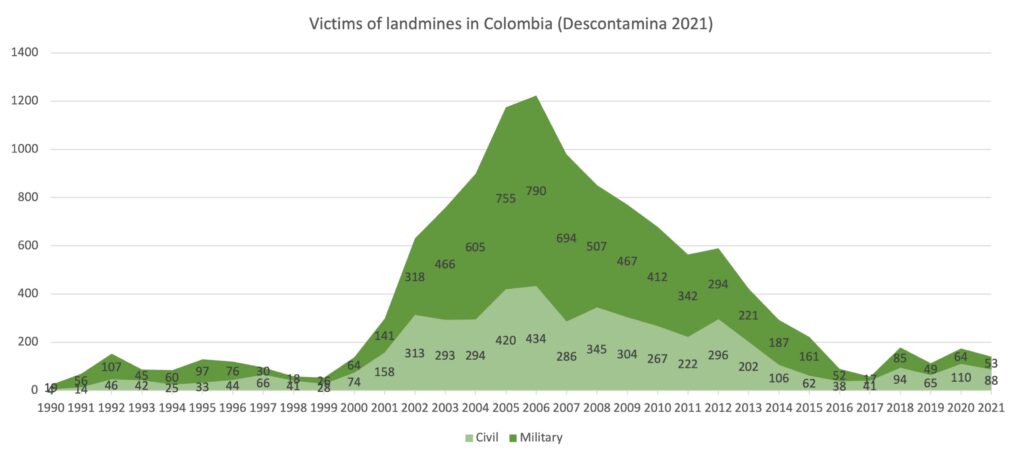

The most biodiverse areas weaponized by landmines in Colombia are protected areas, largely natural parks and forest reservation such as: 1) Parque Nacional Natural Serranía de La Macarena, 2) Parque Nacional Natural Paramillo, 3) Serranía de los Yariguies, 4) Parque Nacional Natural Nevado del Huila, 5) Parque Nacional Natural Sumapaz, and 6) Parque Nacional Natural Tinigua. In these spaces, guerrillas protected strategic assets and built safe havens from which to control the territory, taking over rivers and communication infrastructures. The main target was the army: 60% of victims from 1990 to 2021 are military, corresponding to 7,278 victims killed or wounded by landmines. However, after FARC was demobilized in 2016, the main victims were civilians, including children under 18 years old.

Landmines continue to be a threat in Colombia, and landmined landscapes are not adequately located and marked to prevent new victims. Additionally, there is not enough knowledge of the shape, appearance, and adaptation of landmines to every ecosystem. For example, FARC used tar collected locally to assemble diverse components of some landmines. Tar is a ductile component that can fit into any shape of container or hose: all the circuits, explosives, and shrapnel (see Figure 5). Some other structures use silicon instead of tar, and replace shrapnel with broken glass. Consequently, every landmine adapts to the components of every place, and to the available resources of every military structure.

Research on landmined landscapes can contribute to a general awareness of the complexity of contamination in weaponized natures, while also preventing new victims and damaging practices such as deforestation. Recognizing the role of biodiversity in the process of landmine elaboration allows us to understand the complex relationships inherent within the improvised socioenvironmental technological systems behind these artifacts.

References

Brauch, H. G., & Scheffran, J. (2012). Introduction: Climate Change, Human Security, and Violent Conflict in the Anthropocene. In J. Scheffran, M. Brzoska, H. Brauch, P. Link, & J. Schilling (Eds.), Climate Change, Human Security and Violent Conflict. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace. Springer.

Denyer, S. (2019, August 27). Wildlife thrives among the land mines along Korea’s DMZ. But for how long? Washington Post, 27–29.

Descontamina (2021). Base de víctimas por minas antipersonal. Disponible en: http://www.accioncontraminas.gov.co/Estadisticas/datos-abiertos

Duffy, R. (2014). Waging a war to save biodiversity: The rise of militarized conservation. International Affairs, 90(4), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12142

Duica-Amaya, L. (2020). Paisajes minados en Colombia: los artefactos y su vida natural, social y técnica. Universidad de Los Andes.

Duica-Amaya, L. (2021). La regularización de la irregularidad: paisajes minados y la tecnología local de las FARC para fabricar minas. In Tecnologías de la informalidad y la ilegalidad. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Duica-Amaya, L., & Moreno-Martínez, Ó. (2022). Learning by tradition. Vietnamese technical inheritance in the history of the FARC-EP [forthcoming publication].

Gaynor, K. M., Fiorella, K. J., Gregory, G. H., Kurz, D. J., Seto, K. L., Withey, L. S., & Brashares, J. S. (2019). War and wildlife : linking armed conflict to conservation. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(10), 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.l433

GICHD (2022) The sustainable development outcomes of Mine Action in Colombia [forthcoming publication].

Hallagan, J. B. (1981). Elephants and War in Zimbabwe. Oryx, 16(2), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300017130

Hanson, T., Brooks, T. M., Da Fonseca, G. A. B., Hoffmann, M., Lamoreux, J. F., MacHlis, G., Mittermeier, C. G., Mittermeier, R. A., & Pilgrim, J. D. (2009). Warfare in biodiversity hotspots. Conservation Biology, 23(3), 578–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01166.x

Jasanoff, S. (2004). The idiom of co-production. In S. Jasanoff (Ed.), States of knowledge. The co-production of science and social order (pp. 1–12). Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Marijnen, E., de Vries, L., & Duffy, R. (2020). Conservation in violent environments: Introduction to a special issue on the political ecology of conservation amidst violent conflict. Political Geography, June. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102253

Liliana Duica-Amaya, PhD is a professor of anthropology at Northern Arizona University and a consultant at the Foundation for Conservation and Development in the Colombian Amazon (FCDS) and. the Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD). This article is based on her PhD thesis in Anthropology: Duica-Amaya, Liliana (2020) Landmined landscapes in Colombia: natural, social and technological life of artifacts. Los Andes University. Bogotá, Colombia.