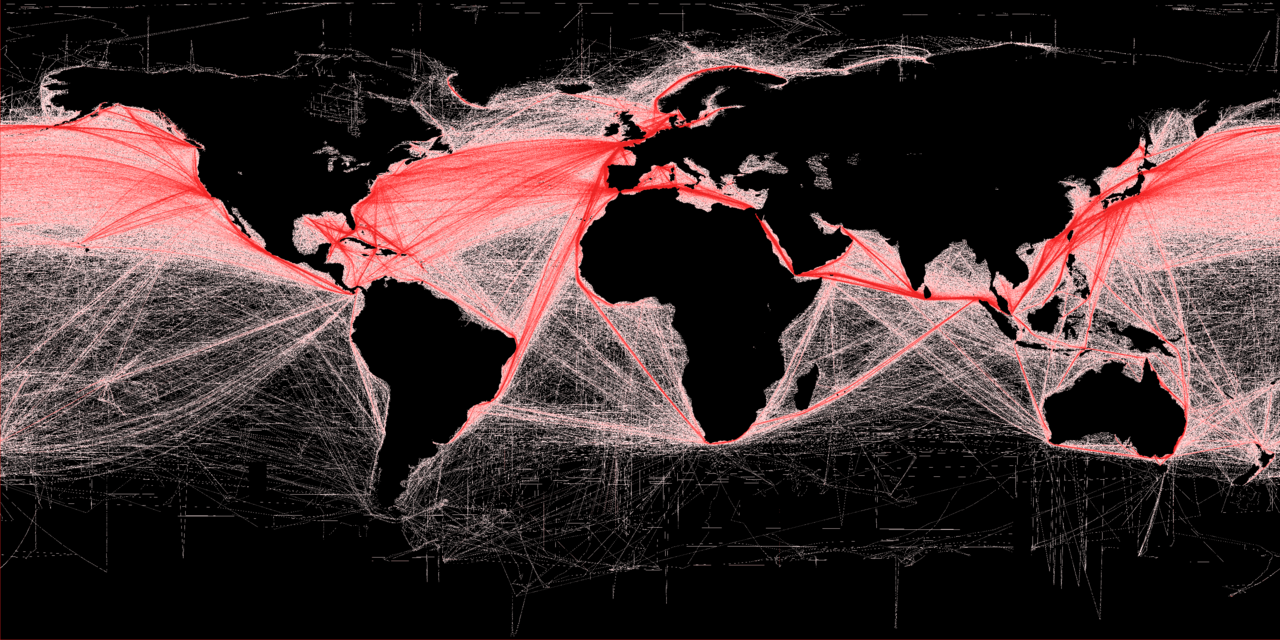

In 2020, the world watched as climate, public health, economic, and racial justice crises converged. It has become increasingly evident that failures of collective and public policies around health and the environment have perpetuated individual suffering. If ever there was an opportunity for the collective to re-think business as usual… it is now. We are firmly situated in the Anthropocene: a time in which human activities are arguably driving our climate and changing environment. The ocean is not exempt from these human influences. Indeed, human energy demands and associated carbon emissions, unsustainable extraction of living and non-living marine resources, land-based activities, and natural processes are contributing to significant changes in marine and coastal environments. These changes include the persistence of plastic waste in most, if not all, ocean ecosystems and species, reduced oxygen and lower pH levels in coastal waters, unprecedented shifts in the range and distribution of marine species, and sustained elevated ocean temperatures over time and space, among others. These conditions exemplify what we are now calling the Anthropocene Ocean. The Anthropocene Ocean is also occurring amidst rapidly changing societies and associated limits to land-based industrial expansion; feeding an emerging narrative about the economic potential of the ocean and its resources (Campbell et al. 2016). Our rapidly changing ocean is also now perceived as the next frontier for growth and expansion of our global economic system.

Read More “Governance for the Anthropocene Ocean”