In Fabian Scheidler’s The End of the Megamachine, he draws on the work of environmental historian Lewis Mumford to show how certain forms of social organization seem machine-like, even if, in the end, they are made up by people. To recognize that the totalizing systems we are forced to engage with daily are not inexorable machines, but the results of an infinite number of decisions by an enormous number of people, can both be depressing or hope giving, depend on how this fact is viewed.

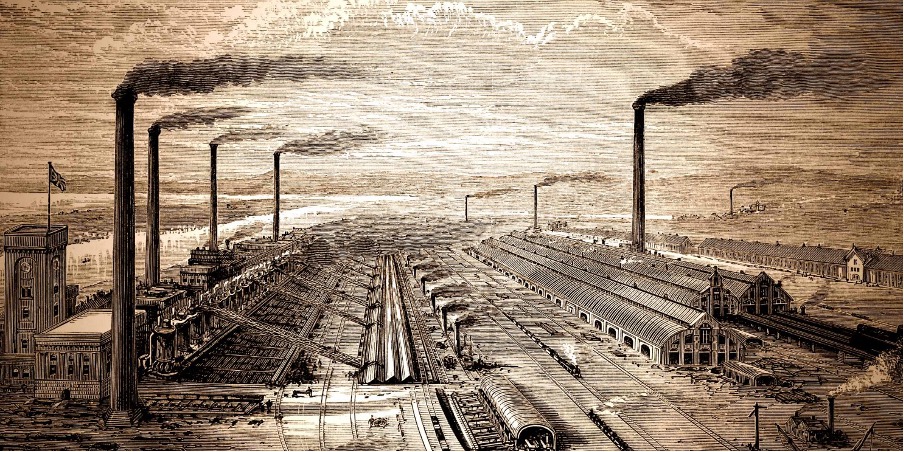

Scheidler’s diagnosis of the megamachine is important, because he focuses on the military need for mining, which lead to industrialization, which has also driven the chemical industry. The corporate-state complex has been predicated on increased control and manipulation of people and the natural environment – colonialism has occurred at countless levels before it has been able to move on to the next. “Before colonizing the world, Europe itself had been brutally colonized,” Scheidler writes.[1] The missionary purpose of religion, doing God’s work by culling infidels and baptizing more and more converts into the flock, served as the template for colonization, which now takes the secularized face of accumulation to support ever increasing disparities in quality of life and lifestyle.

The irony of instrumentalism, even for the highest conceivable good becomes apparent when we look historically at the collateral damage written out of hegemonic discourse. As Scheidler describes it, “[t]he narrative of a mission to save humanity justifies and allows the destruction of other forms of social organization.”[2] These are the casualties of the war on nature: people, places, relationships; all for the sake of a larger secularized religious project of progress. The pretext for the ‘side-effect’ of pollution has been ‘better living through science’ – the always-delayed promise of trickle-down prosperity making the serial sacrifice of the marginalized worth it. Political theorist Danielle Allen describes the democracy-eroding consequences of requiring certain portions of the population to sacrifice for the collective without equitably distributing the costs and benefits.[3] Too often, the expectation of personal sacrifice for the collective gets codified into systematic expectations, creating hierarchies of dominance congealing into discrimination.

Of course, the promised exchange of abundance for ecological destruction is nothing new, but in fact has been a central tenet of extractivism since the mining operations of medieval Europe. In order to see the global displacement of harms from economic centers to economic peripheries as not new, but based on the megamachine permanent war economy of maximum exploitation, Carolyn Merchant reminds us in her The Death of Nature that complaints and gaslighting around environmental injustice existed in pre-colonial Europe as well:

most mines occurred in unproductive, gloomy areas. Where the trees were removed from more productive sites, fertile fields could be created, the profits from which would reimburse local inhabitants for their losses in timber supplies. Where the birds and animals had been destroyed by mining operations, the profits could be used to purchase “birds without number” and “edible beasts and fish elsewhere” and refurbish the area.

Carolyn Merchant [4]

Since the twentieth century, this same logic has been applied to industrialized mining worldwide. Hypothetical future returns justify present damage, including destruction of the ecological basis of local cultures, a phenomenon termed “semiocide” (semiotic ecocide/suicide) for the demolition of meaning that comes from the loss of memory and situatedness associated with habitat destruction.[5]

Phosphorus mining as paradigmatic of extractivism

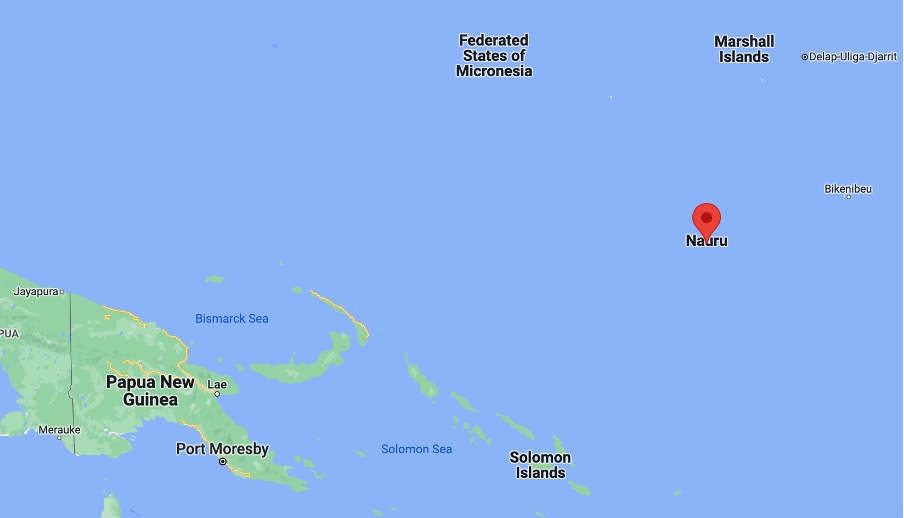

To see how this plays out in recent times, investigating the case of how mining led to ecological destruction, which despite just compensation in a different currency, led to semiocide and the decline of a once vibrant culture, let’s turn to the mining of phosphorus on the island of Nauru.

This fifteenth element on the periodic table accounts for 1% of human body mass, and is crucial for agriculture. In a 1959 essay, Isaac Asimov called phosphorus “life’s bottleneck,” as perhaps more than any other element it determines the carrying capacity for planet earth. Historically, phosphorous-rich human waste was a prized fertilizer, freely available and essential for growing food. Romans used to pay households for collecting their urine to wash the public laundry, as it made an excellent detergent for clothes. But the sanitation revolution killed access to human sources of phosphorous – literally flushing it down the toilet into the sea, where it becomes inaccessible for recapture. This is part of a larger tendency of industrialized humans to take from the earth without giving back, creating what Marx called the “metabolic rift” – the short-circuiting of circular material economies.

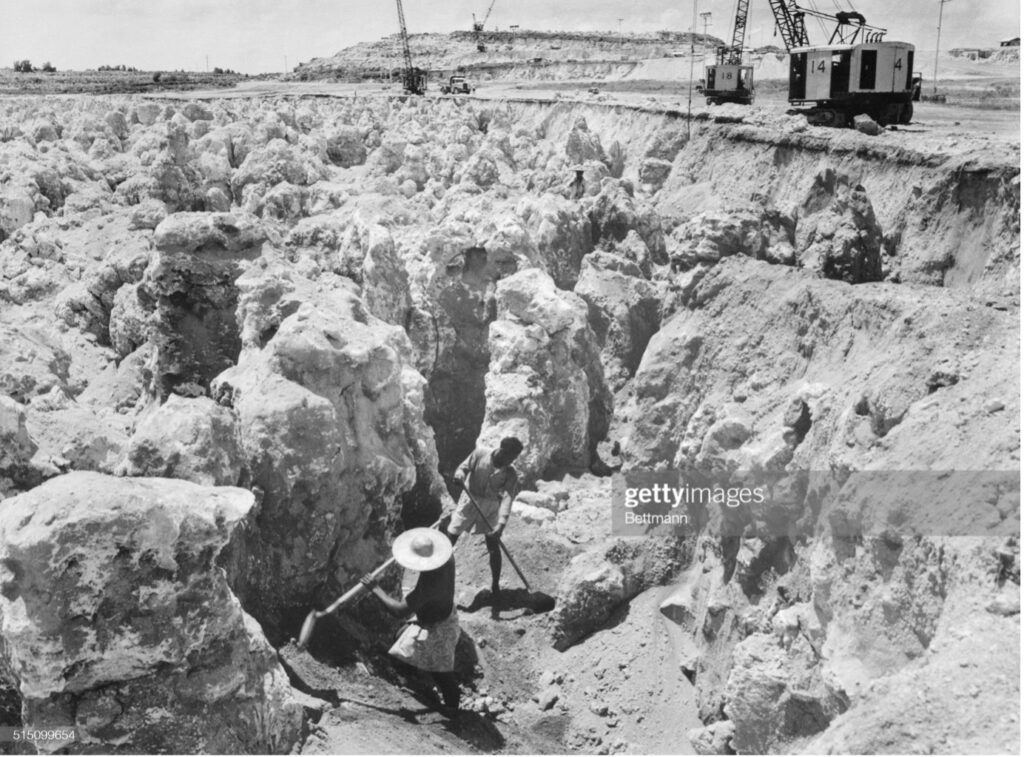

Now, we dig up mountains to mine the same precious element we flush down the toilet. With the discovery of mineral deposits of phosphate rock, these nonrenewable resources temporarily lended an unnatural amount of otherwise scarce renewable resources to grow the human population and unsustainable industrialized practices. (The parallels to fossil fuel (especially oil) extraction are manifold.) Between 1950 and 2000, a sixfold increase in global phosphate-rock production has occurred. Yet, even with mining these deposits, demand is rising twice as fast as supply. And this production has come at astronomical costs.

In 1900 phosphate was discovered on the economically poor but culturally and ecologically prosperous central Pacific island of Nauru. The residents were given an offer too good to refuse – partly because they had little choice in the matter of imperial powers hungry for resources – and in a forward-thinking act at the time, a trust was set up for the island’s 10,000 inhabitants, with the accumulated proceeds from mining to provide income in perpetuity. During the height of the almost century of phosphorous exploitation, the people of Nauru had some of the highest incomes worldwide. However, after the resources were exhausted in the 1990s, and the funds in the trust shrank, the social disintegration and ecological devastation which had been momentarily bracketed and tolerated due to the influx of non-renewable quick money, reemerged like whiplash. About 80% of the once-lush island is totally devastated from phosphate strip-mining, and alcoholism, depression, and diabetes plagues the population.[6] In a 2019 exposé, children interviewed would respond to even simple questions with “I want to kill myself.”

Even all the money in the world couldn’t put the country of Nauru back together again. This is a basic wound in environmental justice that too easily gets overlooked in settlements and post facto compensatory schemes. The Ponzi scheme of exchanging natural “capital” for financial “capital” and pretending that the denominator is the same, instead of an incommensurable exchange, is partly to blame for Nauru being not an outlier, but the paradigmatic case for extractivism. As historian of the megamachine Robert Proctor calls the structured ignorance that makes such unfortunate ‘mistakes’ so common, ignorance is often actively constructed to instrumentalize some people for the sake of others. In other words, the epistemological foundation such schemes are based on are “made, maintained, and manipulated by means of certain arts and sciences.”[7]

Overcoming Regulatory Whack-a-Mole

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The relationships entrenched in mining are paradigmatic but not exceptional for chemical pollution and the strategy of the chemical and fossil fuel industries. For example, a globalized world of trade makes too easy the ball-and-cup street trick of carbon accounting, allowing a false sense of accomplishment when all rich countries have done is export their emissions, rather than reducing them.[8] Whereas Europe and the US suffered unbearable pollution in the 1960s and 70s, now it is Accra, Hotan, Manikganj, Delhi, which are the manufacturing centers, suffering locally the pollution from the production of products exported to richer areas. The Environmental Kuznet’s Curve (EKC) was wrong: pollution doesn’t go down when people are rich enough to realize their industrial culture is killing them—it just gets exported.

This logic of displacement has been long noticed by many astute observers. From indigenous critiques of industrial culture to systems theorists wary of the back-slapping self-congratulations of Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich Democratic (WEIRD) countries,[9] sustainability discourse has too often been cover for NIMBYism.[10] If we are to approach a just transition away from ecocide, this requires NIABYism: Instead of “not in my backyard,” when we acknowledge that pollution is linked to preexisting inequality, we realize that what we really need are coordinated policies that render odious industries “not in anybody’s backyard.”[11] And those who wish to fight for the maintenance of environmental injustice-producing contamination have an imperative to move next to those sources of extraction, those disease-causing factories. If they believe in the sanctity of those industries, then the CEOs of those companies and their shareholders ought to become the fenceline communities to these most harmful point sources of pollution.

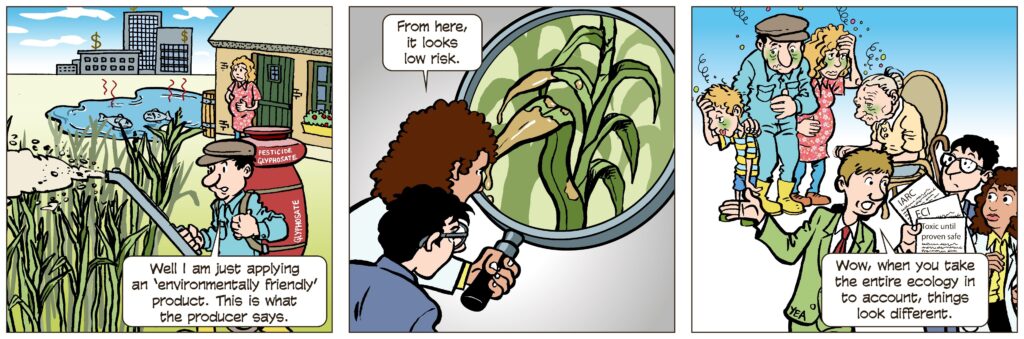

In dealing with the health and ecological harms from chemical exposures, regulators have been behind the curve, playing a game of eternal catch-up. For every after-the-fact regulated chemical, the chemical industry has another stack of chemicals on the shelf ready to deploy to markets. Such is the case with Monsanto’s (now Bayer) glyphosate, which exposed as associated with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, has brought out the even more deadly pesticide dicamba as its replacement. Or, DuPont’s replacement of one PFAS[12] product with another – the endocrine-disrupting ‘forever’ chemicals used in GoreTex jackets and Teflon pans have simply switched a molecule in their organofluorine polymers – we now have GenX instead of PFOAs (Perfluorooctanoic acids, also known as C-8). Such unfortunate substitutions cannot be claimed as victories.

To combat the current Sisyphusian role of chemical regulatory agencies playing “chemical whack-a-mole,” chemical researchers have begun calling for a toxic-until-proven-safe rather than safe-until-proven-toxic paradigm.[13] Many of the chemicals we use currently are shortcuts – they allow unsustainable lives at the expense of others—past, present, and future, human and more-than-human. To get to equity and sustainability, we need to rethink the use, purpose, and place of chemicals in our material environments.

A truly ‘green’ (biocompatible) chemistry needs a toxic-until-proven-safe framework, working to eliminate the worst known chemicals (especially those that cause reproductive health effects and endocrine disrupters, like organophosphates). Additionally, we need to thoroughly reconsider the trade-offs we’ve implicitly accepted for chemical modernism. If we’re to escape the confines of chemical colonialism, we can’t expect to simply switch out different chemicals in an industrial ecology run on toxins based in inequality.

Biomimicry and indigenous materials science needs to be mainstreamed and funded, in order to find nontoxic ways not just of replacing existing toxic chemicals, but to modulate our material environments to not rely on quick and easy disposable chemical-fueled solutions.

References

[1] Fabian Scheidler, The End of the Megamachine (Ridgefield, CT: Zero Books, 2020), 80.

[2] Scheidler, 79.

[3] Danielle S. Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004).

[4] Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 38.

[5] Timo Maran, “Enchantment of the Past and Semiocide. Remembering Ivar Puura,” Sign Systems Studies 41, no. 1 (May 17, 2013), https://doi.org/10.12697/SSS.2013.41.1.09.

[6] John M. Gowdy and Carl N. McDaniel, “The Physical Destruction of Nauru: An Example of Weak Sustainability,” Land Economics 75, no. 2 (May 1999): 333, https://doi.org/10.2307/3147015.

[7] Robert Proctor, “Agnotology: A Missing Term to Describe the Cultural Production of Ignorance (and Its Study),” in Agnotology: The Making and Unmaking of Ignorance, ed. Robert Proctor and Londa L. Schiebinger (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2008), 7.

[8] Lawrence Summers, “The Lawrence Summers Memo,” The Whirled Bank Group, December 12, 1991, http://www.whirledbank.org/ourwords/summers.html.

[9] Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine, and Ara Norenzayan, “The Weirdest People in the World?,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33, no. 2–3 (June 2010): 61–83, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

[10] Leah Aronowsky, “Gas Guzzling Gaia, or: A Prehistory of Climate Change Denialism,” Critical Inquiry 47, no. 2 (January 2, 2021): 306–27, https://doi.org/10.1086/712129; Stan Cox, The Green New Deal and Beyond: Ending the Climate Emergency While We Still Can (San Francisco, CA: City Lights Publishers, 2020).

[11] Yogi Hale Hendlin, “Surveying the Chemical Anthropocene: Chemical Imaginaries and the Politics of Defining Toxicity,” Environment and Society 12, no. 1 (September 1, 2021): 181–202, https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2021.120111.

[12] Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

[13] Alessandra Arcuri and Yogi Hale Hendlin, “The Chemical Anthropocene: Glyphosate as a Case Study of Pesticide Exposures,” King’s Law Journal, September 19, 2019, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/09615768.2019.1645436.

Cover image: “The Iron and Steel Works, Barrow.” Washington Post illustration; iStockphoto

Yogi Hale Hendlin’s work draws on environmental philosophy, especially decolonial kinds, and public health policy, including the corporate determinants of health, to dismantle industrial epidemics. Hendlin is an assistant professor at Erasmus University Rotterdam in the Erasmus School of Philosophy, and Dynamics of Inclusive Prosperity Initiative, as well as Research Associate in the University of California, San Francisco’s Environmental Health Initiative. As Editor-in-Chief of the journal Biosemiotics, Hendlin explores the biological basis for redesigning human systems biomimetically rather than extractively, benefitting both human and more-than-human nature. www.yogihendlin.com

See Dr. Hendlin’s article “Surveying the Chemical Anthropocene: Chemical Imaginaries and the Politics of Defining Toxicity” in the 2021 issue of Environment and Society: Advances in Research, Pollution and Toxicity: Cultivating Ecological Practices for Troubled Times.