The UNFCCC has struggled to be effective in driving ambitious climate action due to several structural and procedural limitations. In the follow up to the Paris Agreement 2015, its reliance on consensus-based decision making has been impeded by divisions between developed and developing and small island nations due lack of inclusivity, lack of accountability, and use of technocratic dominant systems over Indigenous, traditional knowledge systems, etc. (Hermwille et. al., 2015; Kuyper et. al., 2018; Nautiyal and Kinsky, 2022). While the UNFCCC remains the central institution for global climate governance, the efficacy and inclusivity in its pluralistic governance processes are widely debated. Pluralism posits that power in stable democratic nations is dispersed across a variety of actors and not monopolized by more elite actors (Rengger, 2015). In global climate governance, pluralism refers to the coexistence and equality of engagement of diverse actors, systems, values and approaches to address negative impacts of climate change at the global level (Boyd, 2010; de Ridder et. al., 2023; Okereke et. al., 2009). This essay is about whether pluralism exists in practice in the UNFCCC framework of climate governance such that developing and small island countries have equality in participation of the management of the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF). To assess the legitimacy of inclusivity, the essays analyzes pluralism in the Mult-level Governance (MLG) framework of UNFCCC using document analysis and analysis of field observations undertaken by the authors during their participation in three consecutive Conference of Parties (COP) of UNFCCC.

The process of governance of climate change was introduced in 1992 at the UN Rio Summit. It was conceptualized as global governance organization comprising of a broad spectrum of actors working towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (Janicke and Martin, 2017; UN, 1992). It was during this summit that the concept of multi-level governance (MLG) was introduced. The UNFCCC later operationalized MLG as a framework to combat climate change, incorporating national, regional, and local governments, international organizations, the private sector, and civil society (UNICEF, 2020). Geels (2011) and Lundvall (2007) have emphasized the usefulness of MLG in analyzing socio-technical transitions, particularly when dealing with technologies, policies, and institutions. The Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015) exemplifies this approach when it achieved consensus of the signatory parties to the Agreement to agree upon goals, instruments, technologies, finance, and other tools of combating climate change by keeping the global temperature rise below 20C. The Paris Agreement was the first significant multilaterally created climate governance system. Nevertheless, questions persist regarding whether this multilevel structure genuinely empowers all actors, especially small island nations, or if global climate governance is a place for nation states to display their hegemony over other relatively weaker states who may have a seat on the table, but not a share in the pie.

Findings from our research show that UNFCCC’s climate governance process is determined by the extent to which a developed country is willing to bargain its hegemonic power. This hegemonic power is symbolically represented in relative share of developed nation member states vis-à-vis developing nation members in decision making; share of resources provided towards implementation of instruments; and ability to use the UNFCCC process to delay consensus and implementation. The higher the extent to which a developed country cedes power, the better is the chance of achieving pluralism in practice in the governance process. Even though the climate governance landscape exhibits the characteristics of pluralist governance via diversity of actors and multiplicity of initiatives, an actor can dismantle the process if it holds hegemony over other actors.

History and Development of the Loss and Damage Fund (LDF)

Since the first Conference of Parties (COP) in Berlin in 1995, COPs have served as platforms to review climate actions and negotiate global commitments. Climate finance emerged as a key mechanism under this multilevel governance framework. In 1990, the Association of Small Island States (AOSIS) first proposed an international insurance pool to support nations vulnerable to sea-level rise. But the proposal was not accepted, and L&D was not mentioned at the Rio Summit in 1992 because developed countries were hesitant to address financial compensation and liabilities related to L&D (Beylier, 2024). It took over three decades and multiple COPs for this vision to materialize. Incidentally, the Paris Agreement did not contain a formal definition of L&D, which made the process more complex and harder to follow policy-wise, making “non-economic loss and damage (including loss of knowledge, social cohesion, identity, or cultural heritage)” hard to incorporate into the fund (Broberg and Romera, 2020). Nonetheless, there were notable milestones achieved by AOSIS including the establishment of the Green Climate Fund at COP16 in Cancun (2010), the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage in 2022 (Kattumuri et al. 2022), and finally, the LDF agreement at COP27, with operationalization put into effect in COP 29 (Beylier, 2024). These developments illustrate the delayed nature of climate finance negotiations that resulted from divergent vested interests that lead to non-binding negotiations.

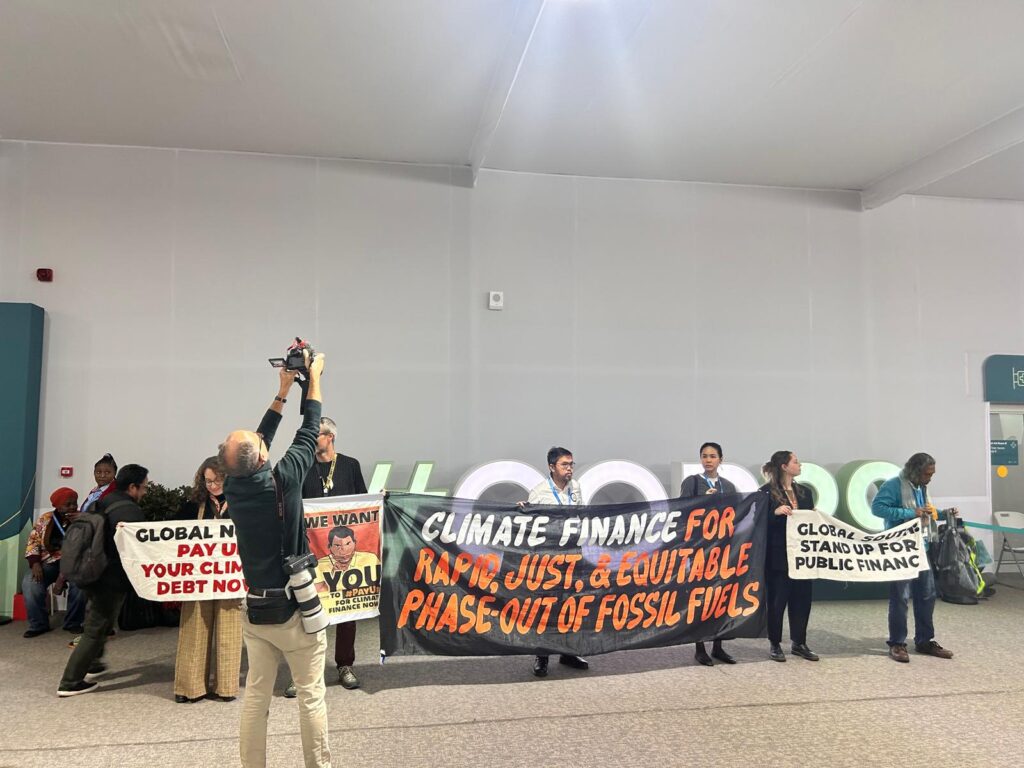

COP29: Observations from the Field

Aritra Chakrabarty, and Alexis Tater, from Michigan Technological University (MTU) had the opportunity to attend COP 27, COP 28 and COP29. While Aritra was part of RINGO and represented MTU as an observer institution in COP 27 & 28, Alexis attended COP29, as part of her study on presence/absence of local indigenous knowledge in climate negotiations. Attending these COPs provided us with a clear understanding as to how negotiations happen at the global scale. We conducted firsthand participant observation of negotiations that happen behind closed doors. Behind each closed door is a political theater that illustrates the pluralistic process. As one moves from one negotiating room to another, you realize that the very existence of this pluralistic process is stalling the negotiation. Negotiated words become promises, which later turn into pledges, and finally result in a report -which thus far has not mentioned “accountability.” While each participatory nation of the Paris Agreement has a voice in the negotiation room, they are not equally weighted in decisions. Also, because the process gives equal chance to every nation, the process is stretched out, proceeding at a slow pace, made even slower when more powerful nations want to “review the motions of an agreement” again and again. The authors observed that the developed countries expressed their power by single-handedly elongating or stalling negotiation processes. Developing nations, and small island nations share the mutual frustration of these delays and on the lack of action on promises made at COPs. For example, the agreement on LDF was achieved in COP 27, 32 years after it was initiated in 1990 by AOSIS. Furthermore, although the COP29 website noted that “significant decisions towards the Fund’s full operationalization” were made, no concrete timelines for disbursement were announced (COP29AZ, 2024). UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres echoed similar concerns, stating that climate disasters disproportionately affect those least responsible and that the initial capitalization of $768 million for the LDF is far from adequate (United Nations, 2024).

Governance of L&D

The LDF is a piece of climate governance instrument made up of an aggregated set of rules, procedures, and precedents, decided upon by a committee using normative elements of negotiation. It reflects different conceptions of what climate finance is; what should do, and therefore does not have a single binding objective nor is binding on any of the nations that have pledged their resources (Nardin, 2000). The operationalization of the LDF exposes the governance gaps in the UNFCCC regime. In March 2025, the United States (U.S) pulled out from the management of the fund with immediate effect (Gastelumendi, 2025). This withdrawal was seen by many state and non-state actors as a major setback to the implementation of the LDF. However, analysis of the status report on the Fund shows that as out of the total $321.24 million received by the Fund as of March 2025, the pledged share of the U.S was only five percent ($17.56 million) which it has paid. On the other hand, the oil resource rich nation of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which had pledged $100 million has provided $25 million so far. The difference in the pledged and the received amount is enormous: $768.40 million pledged is more than two times of the received amount so far. Interestingly, out of the 26 nation states that have pledged to contribute to the LDF, the first and the third largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting nations are absent; both from the list of pledged nations to the committed resources as well as from the membership to the Board of the Fund. The membership of the Board responsible for the management of the Fund also shows a lack of equity in representation. Out of the 26 members, 12 are from developed countries; three from Asia-Pacific states; three from African states; three from Latin American and the Caribbean states; two from Small Island developing states; two from the least developed states; and one from a developing country that is not part of any the above groups. For the small island nations to have only two members, who initiated the conversation and discussion on a funding mechanism back in 1990 represents how hegemonic power makes it way in this pluralistic world of climate governance.

While the U.S exit from the LDF represents only 5% of the total received funds, it’s a symbolic power display that significantly undermines the Fund’s perceived legitimacy. From a pluralist perspective, this action reveals that while the governance framework may appear inclusive, actual influence is still disproportionately concentrated. The U.S exit signals other developed nations who have pledged to the Fund to also reconsider their economic contribution, as there’s no accountability attached with non-commitment. While the Paris Agreement has created universal participation, its mechanism for mitigation and adaption of polycentric framework suffers from higher ambition but low compliance (Falkner, 2016; Torstad, 2020). The process of non-binding voluntary pledges that can be compared and reviewed with the hope of ‘naming and shaming’ as a measure of accountability does not hold ground, as proved in this instance of the U.S exit from the LDF. According to a realist perspective, the voluntary commitment and pledge to the governance process can work if the member nation can gain dominance over other members through that process (Donelly, 2005).

Reimagining Global Climate Governance (GCG)

To make the LDF an effective and just instrument of global climate governance, true to its pluralist foundation, its design must prioritize principles of equitability, accountability, and sustainability (Gurung et. al., 2020). Gurung et. al. (2020) argue that funding arrangements should offer new and additional financial resources beyond existing mitigation and adaptation funds. This distinction is crucial for addressing the unique challenges posed by loss and damage, particularly in vulnerable regions. The success of the Fund lies in navigating these intricacies, aligning financial mechanisms with the dire needs of the most vulnerable, and fostering a collaborative, inclusive approach. The UNFCCC framework, through mechanisms like the LDF, aspires to pluralist governance by involving diverse actors. However, its current structure falls short of enabling genuine influence by small island nations. While these countries have a voice in negotiations, the lack of binding commitments and uneven power dynamics hinder substantive participation. To transform the LDF into an accountable and inclusive instrument, reforms must address these structural inequities and center the voices and knowledge systems of those most affected.

References

- (UNFCCC), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2015). Paris Agreement. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

- (UNFCCC), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2025). Fund for responding to Loss and Damage: Status of Resources. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/FRLD_B.5_6_Status_of_resources_report_of_the_Trustee.pdf

- Boyd, W. E. (2010). Climate Change, Fragmentation, and the Challenges of Global Environmental Law: Elements of a Post-Copenhagen Assemblage. International Environmental Law eJournal.

- de Ridder, K., Schultz, F. C., & Pies, I. (2023). Procedural climate justice: Conceptualizing a polycentric solution to a global problem. Ecological Economics, 214, 107998. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2023.107998

- Donnelly, J. (2019). What Do We Mean by Realism? And How—And What—Does Realism Explain? In R. Belloni, V. Della Sala, & P. Viotti (Eds.), Fear and Uncertainty in Europe: The Return to Realism? (pp. 13-33). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91965-2_2

- Falkner, R. (2016). The Paris Agreement and the new logic of international climate politics. International Affairs, 92(5), 1107-1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12708

- Gastelumendi, J. (2025). The US pullout from the climate loss and damage fund will prove costlier in the long run. Atlantic Council. Retrieved 04/25/2025 from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/us-pullout-from-the-climate-loss-and-damage-fund-will-prove-costlier/

- Geels, F. W. (2011). The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 24-40.

- Gurung, P., Ojha, H., Naushin, N., Singh, P. M., Bhattarai, B., Banjade, P., Adhikari, A., Bartlett, C., Koran, G., & Camara, I. (2023). Designing loss and damage fund: Insights from vulnerable countries. In.

- Hermwille, L., Wolfgang, O., E., O. H., & and Beuermann, C. (2017). UNFCCC before and after Paris – what’s necessary for an effective climate regime? Climate policy, 17(2), 150-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1115231

- Jänicke, M. (2017). The Multi-level System of Global Climate Governance – the Model and its Current State. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(2), 108-121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1747

- Kuyper, J., Schroeder, H., & Linnér, B.-O. (2018). The Evolution of the UNFCCC. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(Volume 43, 2018), 343-368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-030119

- Lundvall, B. Å. (2007). National innovation systems—analytical concept and development tool. Industry and innovation, 14(1), 95-119.

- Nardin, T. (2000). International pluralism and the rule of law. Review of International Studies, 26(5), 095-110.

- Nautiyal, S., & and Klinsky, S. (2022). The knowledge politics of capacity building for climate change at the UNFCCC. Climate policy, 22(5), 576-592. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2022.2042176

- Okereke, C., Bulkeley, H., & Schroeder, H. (2009). Conceptualizing Climate Governance Beyond the International Regime. Global Environmental Politics, 9(1), 58-78. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2009.9.1.58

- Reid, M. G., Hamilton, C., Reid, S. K., Trousdale, W., Hill, C., Turner, N., Picard, C. R., Lamontagne, C., & Matthews, H. D. (2014). Indigenous Climate Change Adaptation Planning Using a Values-Focused Approach: A Case Study with the Gitga’at Nation. Journal of Ethnobiology, 34(3), 401-424. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-34.3.401

- Rengger, N. (2015). Pluralism in International Relations Theory: Three Questions1. International Studies Perspectives, 16(1), 32-39. https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12090

- Tørstad, V. H. (2020). Participation, ambition and compliance: can the Paris Agreement solve the effectiveness trilemma? Environmental Politics, 29(5), 761-780. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1710322

- United Nations (1993). Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. U. Nations. https://docs.un.org/en/A/CONF.151/26/Rev.1(vol.I)

Aritra Chakrabarty obtained his PhD from Michigan Technological University (MTU) in the Environment and Energy Policy (EEP) program in 2025. His research focuses on justice and equity in the renewable energy transition in the in the Global South. Apart from energy and environmental policy, Aritra also engages with climate governance as an issue through on ground interaction with stakeholders across geographies ranging from Europe, Latin America, and Asia. His participation at COP 27 & 28 of UNFCCC provided with on ground perspective of international relations in the context of climate change and how multi-level governance processes work. Aritra is well versed with international relations practices in the context of climate change and energy justice, and his past experience as a renewable energy sector consultant in South Asia, across both sides commercial grids and decentralized solutions gives him the leverage to understand stakeholder negotiations at multiple levels.

Alexis Belle Tater is a new Ph.D. student in Environmental and Energy Policy at Michigan Technological University. Her research focuses on Tribal sovereignty, ethical community engagement, and environmental justice. She is an active member in her community, leading campaigns and protests through Keweenaw Against the Oligarchy (which she founded), creating community spaces for organizing and for people to use their voices in a safe and constructive way. She is also an active leader in Keweenaw Youth for Climate Action, an action-based community and student organization working to urge university divestment from fossil fuels. Her work is rooted in her strong knowledge in and passions for socio-environmental justice and the belief that amplifying Indigenous voices and knowledges is crucial in the fight for climate justice.