Environmental Justice as a Pedagogical Problem

Consider the Park Avenue Elementary School in Cudahy, located ten miles from downtown Los Angeles. Or shift your attention to the Rani Jhansi Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya in east Delhi, a few miles away from the Indian capital city’s most affluent neighborhoods. Though continents apart, what ties these two schools together is their shared exposure and experience to compounding environmental hazards. The former is built on top of a capped unregulated landfill/dump and the latter is surrounded by a massive, operational landfill, an interstate container depot, and waste processing facilities. Students at both schools have experienced adverse health effects related to chemical contamination— developing chronic asthma or even being hospitalized after a gas leak from a nearby container depot.

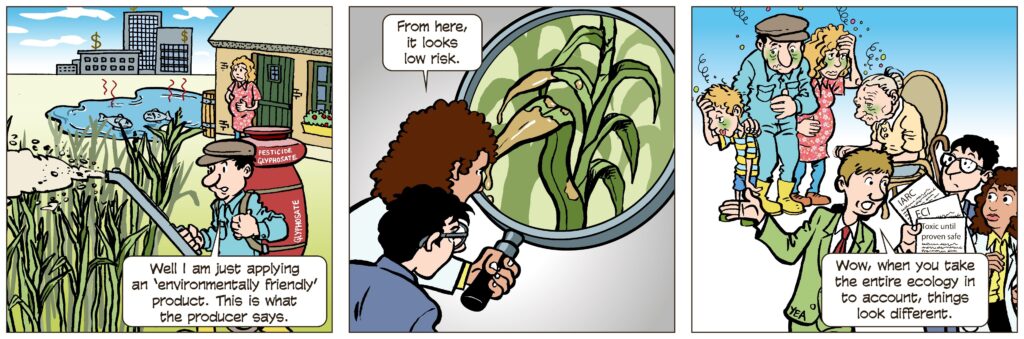

Classrooms and educational spaces can be sites of environmental injustice due to toxic chemical exposure, and classrooms can also be sites of disinformation in which environmental injustice is reproduced. First graders in Oklahoma, for example, read stories about Petro Pete, who had a bad dream in which many plastics in his life – his toothbrush, the tires on his bike, his hard hat – go missing. The message is clear: without petrochemical products, life isn’t good. Along the same lines, in New Mexico, the oil and gas industry leverages their investment in public education infrastructure to push science curricula that uses fracking to teach about the slope of a graph. Across the US, bills are underway that ban even the mention of race and gender in classrooms, which also impacts the teaching of environmental justice and climate change. Production of disinformation and apathy in classrooms extends globally: grade 12 students in Bhopal, India, for example, learn little in their classrooms about the 1984 Union Carbide chemical plant disaster which killed thousands in Bhopal (Iyenagar & Bajaj 2011).

Figure 1. First graders in Oklahoma listen to a story about Petro Pete, who dreams that all by-products of the petrochemical industry have disappeared. He cannot brush his teeth or use soap. He cannot go to school because there is no school bus anymore. Source: Oklahoma Energy Resources Board Homeroom website.

My work contends with how teaching and learning produce and reproduce environmental problems and responses. When something is “stuck”— be it a discourse or a literal cog in the machine— we need to ask what it is that confounds our understanding, and what is the way forward? I will describe here an experimental environmental justice education program in the United States that works within the challenges of a pedagogy in late industrialism, a pedagogy of “cascade learning” that interrogates entrenched structures of feeling and thinking, even as it urges into formation communities of thought and practice that activate learners as stakeholders and stewards of shared environmental futures.

Against Estranged Learning

Environmental justice researchers address complex environmental issues with no straightforward answers or solutions. We examine analytic chains linking polluting industries and racialized governance to habits of thinking and doing— examples of what anthropologist Kim Fortun calls “late industrialism”, necessitating “modes of thought, collaboration and practice that we haven’t yet figured out” (Fortun 2012). In my research on the ways scientists, environmental advocates, and entrepreneurs are responding to the enormous socio-ecological and political complexity of air pollution in Delhi, I worked with urban studies scholar Rohit Negi to understand how their responses were shifting habitual ways of thinking and doing science, advocacy, and corporate responsibility (Negi & Srigyan 2021). We were frequently asked to explain our ethnographic research to diverse audiences, with people listening carefully to understand how our expertise can be useful for them. Turning to pedagogy is one way to do that— even more so when spaces of education become critical sites of environmental injustice.

Figure 2. The EcoEd Research Group website. Source: The Asthma Files.

The EcoEd program is a learning collective that started in 2012 at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, bringing together university-based faculty and undergraduate and graduate students to address the challenges presented by late industrialism. A persistent challenge of late industrialism is to understand environmental injustice as a multi-scalar and complex problem. To respond to this challenge, the program’s evolving list of literacy goals include recognizing complex causation, cross-scalar relations, organization and analysis of information, collaborative tactics, and creative strategies to communicate research findings, developing what anthropologist Angela Jenks calls “justice-oriented civic capabilities” supporting students in their transitions as social agents (Jenks 2022).

And there are compelling reasons to advocate for these literacy goals. Learning to recognize and understand where things get stuck— and how to get them moving towards different ends so that systems (and people) don’t repeat what they always have— is what Gregory Bateson calls deutero learning or “learning to learn.” To understand how pedagogy reproduces environmental injustice, and how it can be a pathway to address it, deutero learning requires deep thinking, doing, and enacting a series of experiments to figure out what can work and what cannot. There are a number of pathways that don’t work: for example, we know through the works of educators Paulo Freire (1968) and bell hooks (1994) that commodification of learning in silo-ed off institutions has produced teachers and learners to become invested in the “banking model of education”, framing an educator as a transmitter and a learner as a passive recipient of knowledge.

The model fails in part because learners are obviously not passive, and educators are always doing more than mere “transfer.” Resistance to learning and teaching emerges in a skewed and stuck dyadic relationship. It also fails because it positions learners as opposed to one another, where the possession of knowledge becomes something that causes worry rather than excitement. Learning theorists Jean Lave and Ray MacDermott (cite) call this “estranged learning”, reading Marx’s theory of estranged labor to understand how alienation (of work from the worker’s body, of time from narrative, of the self from the world, of categories from their meanings) produces subjectivities of learning and teaching that actively resists coming together for reflection and conversation. In places where settler/colonial logics have set forth racialized, classed, and gendered ways of thinking and being (Grande 2015, Shange 2019), estranged learning maintains barriers that prevent collective reflection and action.

Estranged learning means that students are learning that petrochemical products are here to stay, and are being socialized to ignore or tolerate compounding factors. They are not learning about how their bodies and neighborhoods are affected by the oil and gas industry. They are not learning to dream about alternatives to fossil fuels. Combined with the banking model of education’s skewed-and-stuck knowledge transfer paradigm, estranged learning means that learners will in fact be resistant to such change—which is one reason why “straight facts” don’t work, especially in a post-truth age where “which truths count and which are ignored is a central question” (Davies & Mah 2020). Cultivating justice-oriented civic capabilities is then a matter of undercutting mechanisms that produce estranged learning. The question then becomes: which pedagogical tactics cultivate this capacity?

Cascade Learning in EcoED

The EcoEd program enrolled undergraduate students to be mentors to elementary and middle school students. In their roles as mentors, undergraduate students developed and communicated research projects about environmental issues through undergraduate courses like Sustainability Education. By analyzing existing environmental education programs and curricula in the US, they designed curriculum modules and lesson plans that connected local issues to global networks. A curriculum module for K-5 on watersheds and environmental sustainability, for example, also provided a lesson on local, regional, and global flows of resources by having students “visualiz[e] problems, consequences, sources, and solutions for watershed pollution in their towns” (Balas 2012). This lesson was followed up with a poster presentation session where students communicated their findings about watershed pollution with a message on why water conservation is important. As a whole, the module cultivated creative research and communication skills, and positioned K-5 students as environmental stakeholders.

Figure 3. A group of second grade students write out the plot of children’s book “Michael Bird Boy” and show how air pollution is in the book. Source: The Asthma Files.

By activating the capacity of a learner to see themselves as stakeholders with investment in an environmental issue, cascade learning sets off “communities of practice” (Lave & Wenger 1991) with shared literacy and research goals. Picture books and news shows created and curated by elementary and middle school learners cultivate storytelling practices that are also imaginative and speculative spaces to inscribe and enact responses and solutions. Consider the picture story produced by elementary school students Nicholas and Andrew: based on the illustrated story Michael Bird-Boy by Tomie dePaola, the story “Nicholas Bird-Boy” considers a range of solutions to address the air pollution coming from a factory that makes teddy bears and dolls in their town.

By learning how to identify the problems of late industrialism with K-5 learners, undergraduate students become researchers and educators in their own right, seeing where things become stuck through pedagogical practice. This is “cascade learning”, “wherein university students come to really understand the conceptual and cultural challenges posed by environmental problems by really thinking through how to cultivate capacity to deal with those challenges in younger students.” (Reddy & Fortun 2014).

Figure 4. Grad student teaching first and second grade students the children’s book “Michael Bird Boy” and the environmental aspects of it. Source: The Asthma Files.

Placed in cascading communities of practice— as researchers, journalists and storytellers— learners come to see themselves as social and political agents, learning how their research findings are meaningful to diverse publics, both anticipated or unanticipated. By co-designing curriculum modes and enacting them with younger learners, undergraduate students learn to see environmental issues as pedagogical problems that will not be resolved merely by putting the facts out there, or assuming knowledge will go where it is supposed to go, reach who it is supposed to reach, or be learned and taught in specific ways.

Teaching Outside the Lines

Organizing programs like EcoED requires significant investment from a community of researchers, educators, and parents willing to cultivate life-affirming, civic-oriented, experimental sensibility in themselves as learners and in people they will teach. The unsettling of sedimented ways of thinking and being that this process induces could itself produce inertia. In I Love Learning; I Hate School, anthropologist Susan Blum notes the extractive desire constitutive of estranged learning: students want to get “learning” out of their way to get to somewhere else, and teachers aim to get “learning” out of students to see their role as educators fulfilled (Blum 2017). The challenge of cascade learning is to be in productive tension with this extractive desire and reorder it to reflect critically on how we learn to learn and to teach.

Intersecting injustices produced by the abandonment of communities to extractive resource and governance relations actively undermine capacity building in communities. As educators, we need to teach our students to analyze sources of mistrust, disinformation, and active harm in their communities. We also need to teach them how to find ways of moving forward. The challenge in cascade learning is to push back against entrenched and internalized characterizations of communities and their residents.

Environmental justice pioneer Charles Lee calls this the challenge of “second-generation environmental justice”, identifying, characterizing, and integrating the analysis of disproportionate burdens, systemic racism, and cumulative impacts that renders communities highly vulnerable to environmental harm (Lee 2021). How can cascade learning contend with broader community capacity, especially when it has been actively and intentionally undercut? What pedagogies can illuminate long histories of resistance and organizing against supremacist and extractive logics? At a time when learning is more estranged than ever, what pedagogical tactics can nourish learners and communities in their capacity as people with tools, skills, and resources necessary to make the way forward?

References

Balas, Erin., 2012. “EcoEd Curriculum RPA Watersheds Curriculum.” Personal Communication.

Blum, Susan D. 2017. I Love Learning; I Hate School: An Anthropology of College. Cornell University Press.

Davies, Thom, and Alice Mah, eds. 2020. “Introduction: Tackling Environmental Injustice in a Post-Truth Age.” In Toxic Truths. Manchester University Press.

Fortun, Kim. 2012. “Ethnography in Late Industrialism”. Cultural Anthropology 27(3): 446-464

Freire, Paulo. 1968. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Bloomsbury Press.

Grande, Sandy. 2015. Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought. Rowman & Littlefield.

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Iyengar, Radhika, and Monisha Bajaj. 2011. “After the Smoke Clears: Toward Education for Sustainable Development in Bhopal, India.” Comparative Education Review 55 (3): 424–56.

Jenks, Angela. 2022. “Reshaping General Education as the Practice of Freedom.” In Applying Anthropology to General Education, edited by Jennifer R. Wies and Hillary J. Haldane, 61-79.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, Jean and Ray McDermott. 2002. “Estranged Labor Learning.” Outlines 1: 19–48.

Lee, Charles. 2021. “Confronting Disproportionate Burdens and Systemic Racism in Environmental Justice Policy.” Environmental Law Reporter, 19.

Negi, Rohit, and Prerna Srigyan. 2021. Atmosphere of Collaboration: Air Pollution Science, Politics and Ecopreneurship in Delhi. Taylor & Francis.

Reddy, Beth and Kim Fortun. 2014. “Doing Critique in K-12: Kim Fortun on Ethnography, Environment, and the EcoEd Research Group”. Platypus: The CASTAC Blog.

Shange, Savannah. 2019. Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness, and Schooling in San Francisco. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Prerna Srigyan is a PhD researcher studying education to science and governance pathways, focusing on environmental and social justice education. She is developing a range of collaborative projects on science, STS, and pedagogy using ethnographic and archival research methods. She works at the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine.