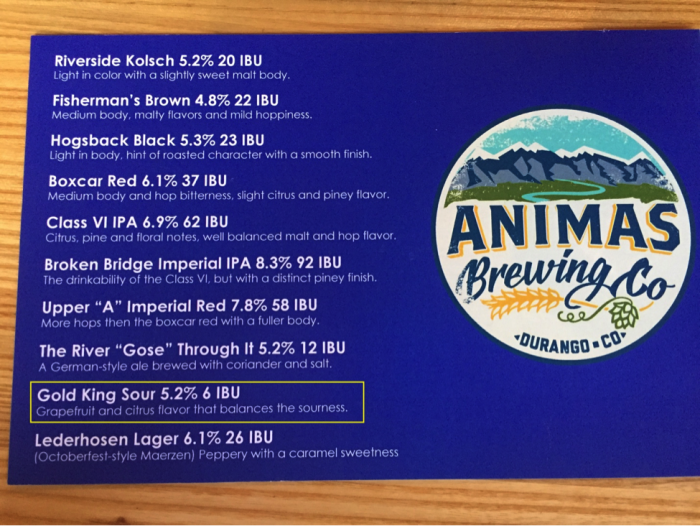

On 5 August 2015, a contractor working for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) accidentally breached a plug of waste rock at the Gold King Mine near Silverton, Colorado. Unbeknownst to the backhoe operator responsible for the breach, the plug was holding back three million gallons of acid mine drainage laced with numerous toxic metals such as zinc, cadmium, mercury, lead, and arsenic. Within hours, the yellow-tinged toxic waters from the Gold King Mine spread downstream from Cement Creek into the Animas River, eventually making their way into the San Juan River until being diluted by their entry into the Colorado River. En route, the waters heavily impacted the livelihoods of farmers, fly fishing guides, and rafting companies from Durango, Colorado, to the Navajo Nation in northern New Mexico.

The Gold King Mine spill brought international attention to the plight of abandoned mine lands (AMLs) in Colorado and elsewhere in the Western United States. Colorado alone has more than 23,000 abandoned mines, and there are estimated to be close to 500,000 in the United States, mostly in the West. While coal mines have been required to clean up their operations since 1977, the same is not true for hard rock mines, which are protected from environmental liability under the General Mining Act of 1872. Many of Colorado’s hard rock mines ceased operating in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, yet hundreds (perhaps thousands) still release acid mine drainage (AMD) formed by sulfur-bearing rocks coming into contact with air and water. Other AML sites have waste rock and tailings piles that come into contact with streams and other forms of surface water increasing the loading of heavy toxic metals into waterways. Metal loading severely impacts the health of streams, killing fish and macroinvertebrates, leaving large stretches of some Western rivers lifeless for miles.

With no source of federal funding like the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 that governs the cleanup of coal mines, the reclamation of legacy hard rock mines depends on a variety of actors and mechanisms including individuals, mining companies, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), states, tribes, and the federal government. Funding comes from a variety of sources including the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA, aka Superfund), the Clean Water Act (CWA), and other watershed recovery funds. However, hampering the efforts of many of these entities during reclamation are the liabilities and fines that can be brought against them if they fail to bring water quality standards up to the levels required by the CWA (e.g., even if a highly toxic site were brought to within 90 percent of CWA standards, the entity initiating the cleanup could be sued). As such, many of the most polluted AML sites remain untouched for fear of litigation and liability in perpetuity. Efforts to introduce “Good Samaritan” legislation that provides legal protection for people attempting legacy mining cleanup have repeatedly failed in Congress in what one Colorado news outlet has called a battle of “greens against greens” as major environmental NGOs oppose such legislation because of the precedent of waiving compliance under the strictures of the CWA.

For many communities, the prospect of being listed as a Superfund site carries concerns about the viability of future mining projects, as well as impacts on tourism and the involvement of the federal government. The first community downstream of the Gold King Mine is Silverton. Residents and town officials for years fought Superfund designation, which the government recommended because of AMD from the Gold King and dozens of other mines in the upper Animas River watershed. With the end of mining in Silverton in 1991, the town is entirely dependent on tourism dollars, and fears that Superfund listing would diminish the economy were prevalent. Yet, with the Gold King spill, the mining district upstream from Silverton was declared a Superfund site in September 2016. For many people, the fact that the entity that caused the Gold King spill—the EPA—would also be the same entity overseeing the reclamation of the newly listed Bonita Peak Mining District Superfund site was problematic. In fact, the month before the listing, the Navajo Nation announced it was suing the EPA in its role for causing the Gold King Mine spill.

In April 2017, I started attending biannual town hall meetings held by the EPA in Silverton, Durango, and Farmington. My research is intended to address the political ecology of risk related to environmental contamination. At stake is a concern to understand how people collectively respond to and mitigate (or not) environmental risks. My research project is a comparative study of community (including interactions with NGOs and government entities) responses to legacy mining pollution and reclamation in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado. The San Juans have been the site of hard rock mining since the 1870s, involved the displacement of the Ute Nation from their ancestral homelands, and thus provide an exemplary case study of the legacies of the 1872 mining law, settler colonialism linked to mining, and contemporary efforts to deal with mining pollution and reclamation. The region offers a variety of community-led efforts to deal with mining cleanup, with several of the communities at some point in the process of Superfund listing. As I argue in a forthcoming article on the anthropology of mining in the Annual Review of Anthropology, the structure of our very lives consigns us to living in the Mineral Age. Finding creative, collective efforts to better deal with the social and environmental impacts of life in the mineral age are imperative for the sustainability of our planet and the social-ecological systems that depend on it.

Jerry K. Jacka is an Associate Professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Cite as: Jacka, Jerry K. 2018. “Abandoned Mine Lands and Collective Cleanup Efforts.” EnviroSociety, 18 June. www.envirosociety.org/2018/06/abandoned-mine-lands-and-collective-cleanup-efforts.