bears ears |berz irz| (noun) def. (1) the organs of hearing in a bear; (2) a geological feature over 8,700 feet tall consisting of two sandstone buttes in southeastern Utah; (3) a prominent landmark featured in the sacred geography of several Native American tribes in the Four Corners region of the United States; (4) the newest National Monument in the United States that has become central to struggles over land rights in the western United States

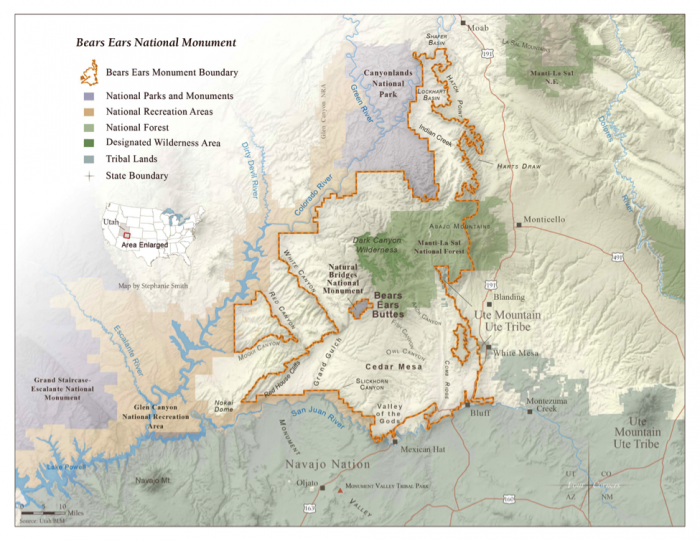

On 28 December 2016, US President Barack Obama used the Antiquities Act to designate a 1,351,849 acre National Monument called Bears Ears in southeastern Utah. In his public statement, he did so

to protect some of our country’s most important cultural treasures, including abundant rock art, archeological sites, and lands considered sacred by Native American tribes. Today’s actions will help protect this cultural legacy and will ensure that future generations are able to enjoy and appreciate these scenic and historic landscapes. Importantly, today I have also established a Bears Ears Commission to ensure that tribal expertise and traditional knowledge help inform the management of the Bears Ears National Monument and help us to best care for its remarkable national treasures.

Within a week after taking office, President Donald Trump met with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) to discuss his “eagerness” to begin work on undoing the “travesty” of protecting these sacred lands, as reported in The Washington Post. And to that end, on 26 April 2017, Trump signed a Presidential Executive Order on the Review of Designations Under the Antiquities Act, declaring that all designations of National Monuments of areas greater than 100,000 acres made since 1 January 1996 would come under review. Quite tellingly, Bears Ears is the only National Monument specifically mentioned in the executive order.

The management of Bears Ears is unique in that it includes the formation of a five-person tribal commission—the Bears Ears Commission, comprising one member each from the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah Ouray, the Hopi Nation, the Navajo Nation, and the Zuni Tribe—to partner with the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service in overseeing the monument. The inclusion of Native American knowledge and opinions has never been done in the history of public lands management in the United States. The singling out of Bears Ears in Trump’s executive order as such is deeply troubling for a number of reasons

As Patrick Wolfe (2006: 387) writes in “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of The Native,” “contests for land can be—indeed, often are—contests for life.” The outcomes of land contests often depict whose lives are considered more important. I think about this constantly as I drive across the landscape of the US West. In the Lower 48 western states, about 47 percent of the total land area is public land. This is just less than 350 million acres, an area of land about the size of Alaska, or an area of land that includes not only the entire Eastern seaboard, but also the states of West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama. Today, as one drives through these 350 million acres of land, often all one sees are a few rangy cattle, a whole lot of trees, and vast deserts. These public lands are part of the 750 million acres of land making up the 11 western states that were seized from Native Americans. As I drive past a few head of cattle scattered across a vast arid landscape, I can’t help but ask, “And we forced the Native Americans off this land and onto reservations for what purpose?” The purpose, of course, as Wolfe notes, has to do with “the logic of elimination.” Settler colonialism “strives for the dissolution of native societies,” and the settler “invasion is a structure not [a one-off] event” (388). Transforming Native lands into public lands is an obvious process of “accumulation by dispossession” (Harvey 2005; West 2016) that perhaps generates some income for the US government, but largely underwrites the Western myth of self-sufficiency, a myth that is increasingly being challenged in new ways.

Shifting cultural and economic winds in the western US are changing how people think about and relate to the land. The demise of ranching, mining, petroleum development, and logging has left many people blaming public lands and the federal government for the dire economic circumstances that face many western communities. Witness the recent occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon in which the leaders of the illegal occupation claimed to be demonstrating in order to return the lands to their rightful owners. As Burns Paiute tribal chair Charlotte Roderique said in exasperation over this claim, “I’m sitting here trying to write an acceptance letter for when they return all this land to us.”

The attack on public lands is also taking place on the state government level, led by Utah’s congressional delegation. Rep. Rob Bishop (R-Utah) as the chair of the House Natural Resources Committee has long been leading a fight for the Public Lands Initiative as an attempt to turn protected federal public lands over to the state of Utah in order to allow increased resource extraction and detrimental uses of the land. Luckily, his proposed bill failed to come up for a vote in last year’s House of Representatives. It only had one other supporter in the house, Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah), and no Senate supporter. Nevertheless, Utah’s congressional representatives intend to keep trying. On 24 January 2017, Chaffetz submitted H.R. 621, which would have transferred 3 million acres of federal lands to western states. The bill was pulled a week later because of outcry from conservationists, hunters, hikers, and multitudinous others desiring public lands to remain public.

In response to Utah’s leaders’ stance on public lands, the Outdoor Retailer trade show announced it would be abandoning Salt Lake City as the site of its lucrative annual show after 20 years. The Outdoor Industry Association and executives from REI, the North Face, and Patagonia had warned Utah Gov. Gary Herbert to abandon efforts to transfer public federal lands to the state. This alone cost the local economy in $45 million in direct spending from the trade show. Moreover, a study done in 2014 by Utah university economists projected that the cost to manage these lands would total almost $280 million in 2017—most of which would be used for wildfire-related expenditures. A poll conducted in 2017 among voters in Arizona, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming found that 58 percent of people opposed transferring control of federal lands to states.

In late March 2017 over spring break, I drove to Bears Ears to see for myself the contested landscape. I backpacked into Dark Canyon Wilderness, a designated Wilderness Area in the heart of the national monument. My car was the only car at the trailhead. As the route into the upper canyon was blocked by snow, I had the 47,000-plus acre wilderness area to myself that night. The following day I picked my way carefully up the narrow, trail-less canyon. As I sat and ate lunch, the only sounds I heard were canyon wrens, ravens, and the occasional overhead jet. Canyon wren … [long pause of silence] … canyon wren … [long pause of silence] … jet … canyon wren. The purpose of national monument designation is to prevent the new development of mining, oil exploration, and grazing; existing rights are still valid. I chewed my trail mix and thought back to two different trips I took through northern New Mexico a few years back. In March 2013, I drove to Chaco Canyon to see the amazing ancestral Puebloan ruins. It was an uneventful drive to the canyon. The following year in March 2014, I drove the same route again (US Hwy 550) on my way to Dark Canyon Wilderness in an unsuccessful attempt to hike in on the upper canyon route (too much snow again). The area around Chaco had been completely transformed by fracking development. What had been a serene, peaceful landscape the year before was now choked with mining rigs, trucks, and the burning flare-offs of methane from the fracking process. I was thankful that the Bears Ears region would not suffer the same fate.

After a few days in Dark Canyon, I hiked out and drove to Natural Bridges National Monument—itself now surrounded by Bears Ears National Monument. Natural Bridges is located on the Cedar Mesa Plateau, named for the creamy white, 250-million-year-old sandstone capping the plateau. Humans have been living in the canyons around Cedar Mesa for more than 10,000 years—from Clovis people to Basketmaker to Puebloan to modern-day Native Americans and Euro-Americans. Most of the 56,000-plus archaeological sites on Cedar Mesa were left by ancestral Puebloans. Thousands of rock art images and panels decorate the canyon walls. Before its designation as part of Bears Ears National Monument, Cedar Mesa was America’s largest and most significant unprotected archaeological site. That night, I camped on the cliffs above Natural Bridges—courtesy of the thousands of free, informal campsites dotting our public lands.

The proclamation designating Bears Ears National Monument is a document that the nature writer Terry Tempest Williams points out is “more akin to poetry that public policy.” She notes that to merely read the opening sentence of each paragraph is to read into a poem depicting the geology, anthropology, ecology, and history of a truly amazing place. She writes:

What appears is a region so vast and mysterious where the handprints of past people can still be found on canyon walls, a landscape so chockful [sic] of earthly delights, why wouldn’t we as modern-day stewards move to protect it? … The proclamation of Bears Ears National Monument reminds us what native people have never forgotten: We are not the only species that lives and loves and breathes on this planet we call home.

Places like Bears Ears, islands of green in a red rock landscape, that capture water from the storms, the Navajo (Diné) called nahodishgish, “places to be left alone.”

To close this essay, as I mentioned, the public lands in the western United States are the shameful legacy of a century and a half of settler colonialism. As I write these words, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke is flying over the Bears Ears region as part of the executive order reviewing the designation of National Monuments. The creation of Bears Ears National Monument was a small step toward rectifying this legacy of removing people from their homelands. I doubt that the people of the United States have the political will to actually return the public lands to the indigenous groups who once lived on them. The next best thing to that, though, is to ensure that these stunning landscapes remain in the commons, public lands owned by us all, protected by us all, and used by us all in ways that ensure they will remain for future generations.

Dr. Jerry K. Jacka is Assistant Professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder. His book Alchemy in the Rain Forest: Politics, Ecology, and Resilience in a New Guinea Mining Area (Duke University Press, 2015) draws on theories of political ecology, place, and ontology and ethnographic, ecological, and spatial methods to examine the making of a resource frontier in the Porgera Valley, PNG. His work has been supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research and the National Science Foundation.

References

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

West, Paige. 2016. Dispossession and the Environment: Rhetoric and Inequality in Papua New Guinea. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409.

Cite as: Jacka, Jerry K. “Bears Ears: In Defense of Public Lands.” EnviroSociety, 17 May. www.envirosociety.org/2017/05/bears-ears-in-defense-of-public-lands.