Superfoods and superfruits are terms we have increasingly become accustomed to. Although these terms are variably defined (click here, or here, or here), as their names suggests, these are foods that are marketed as being nutrient rich. In fact, one website touts these foods as “ancient abundant energy,” claiming that they provide the “planet’s best and most powerful” sources of “natural nutrition.” The “superfood” term does not originate from dietetics or nutritional science but is in fact widely understood as a clever marketing tool.[1] Despite the relative lack of evidence to support claims of these foods as the “most powerful,” the superfood trend remains a powerful attracting force. For example, you would be hard-pressed to find someone willing to pay more than $5 for a blueberry smoothie, but if you called it a “superfood smoothie,” my guess is that many urban gym goers would be convinced that their breakfast shake is providing them with all the nutrients and energy that they need for the day, and therefor they might not be bothered by a higher price tag. If I were reading this right now, I would be asking “And so, if a wealthy urbanite wants to spend $8 on a smoothie, how is this an issue that should feature on a blog focused on environment and society?”

Marketing food items in such a way, as an “ancient abundant energy” source, is problematic. Two major issues arise in the marketing of these products; the first is the fact that such products are not “discovered” by the clever companies marketing these products. In fact, the use of many of these products emerges from the local ecological knowledge of people living off and through the environments in which they dwell. As such, the income generated from the sales of such items should benefit the populations where this knowledge originates, yet we have seen countless cases of similar bio-piracy where the only beneficiaries are the corporations marketing the products (e.g., Hoodia and Rooibos).

The second issue that arises in the context of the extensive marketing of superfoods is that, in many cases, these food products are either important nutritional supplements or staples in diets of indigenous or marginalized populations. For example, my research among edge-dwellers living on the boundary of a South African protected natural area (PNA) highlights the ways the increased marketing of these foods may come into conflict with a key nutritional source of the local residents. Edge-dwelling refers to people residing on the borders of nature reserves or protected natural areas (PNAs). When conservation legislation limits edge-dwellers’ access to lands that they formerly used to source important nutritional resources, their needs are subordinated to the goals of conservation protectionism (Brockington et al. 2008; George 1998 in Anderson and Berglund 2003: 6). The assignment of “protected” status imposes restrictions on land use practices, which includes resource access, with concomitant impacts on food gathering practices and nutrition.

In my research setting, a rural village in South Africa’s Limpopo province, edge-dwellers’ access to important nutritional sources has been increasingly regulated and constrained as a result of their edge-dwelling status. For example, customary practices of hunting have been made illegal—creating poachers out of those who were formerly hunters. In addition, other protein sources, such as mopane worms and termites, are increasingly difficult to source, as the fences that delineate the boundaries to the PNAs limit foraging areas for termites and access to mopane trees. Decreasing the lands through which people are permitted to forage and gather also increases competition, thus intensifying food insecurity. In such a setting, alternate nutritional sources are needed. My research has revealed that “wild” or non-domesticated fruits are an important source of nourishment and are, in fact, a favored source due to their “wild” nature, lacking chemical interventions. In this context, baobab (Adansonia digitata), a “wild,” non-domesticated fruit, is a local food source of high importance. It is a key resource for local remedies when children fail to thrive and provides people with “yogurt-like” alternatives that do not demand refrigeration. It is a vital source of vitamin C in a setting that is a veritable food desert[2] and contains potassium, magnesium, and high levels of calcium (Osman 2004).

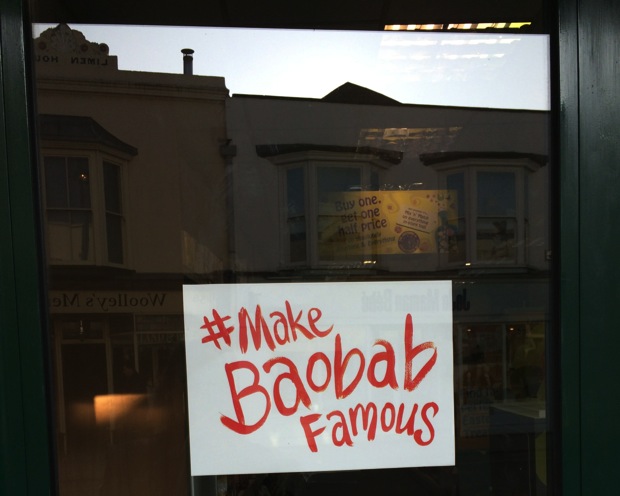

So, imagine my surprise when, early in April, while walking down the high street in an English town, I saw a health food chain store imploring passersby to help them “#MakeBaobabFamous.” This, added to the growing list of places I had seen baobab products for sale, from Cape Town to Germany, sparked a concern in me: that products central to nutritional vitality in this already resource-squeezed setting will become increasingly unobtainable as baobabs become “famous.” Other products unique to regional locations, like quinoa and goji berries, have been made so “famous” as to make them unobtainable to local users, while making those local users (indentured) farmers for a growing international market (Ballet and Carimentrand 2010; Jacobsen 2011). This raises the question of what will happen to the edge-dwellers in my research site as baobab becomes famous? Over the past year, with this concern in mind, I began to collect information on the costs of baobab powder (see the table below for a truncated list):

Baobab Powder Prices (2015/2016)

100g = R62.50 (South Africa)

100g = 7.49 euro (Germany)

100g = 5.99 pounds sterling (UK)

The growing list of products and companies marketing baobab, from cosmetics to food supplements to dried snacks, forces me to ask many questions with my research site in mind. First, how can we stop this “bio-piracy”? This is a question that others have been trying to address for many years (see Chennels 2001 for Hoodia-related case studies) with very little luck. So perhaps a more productive step forward would be to ask all of you to reflect on your own purchases and be cognizant of the impacts of purchasing these nutritional powerhouses. In so doing, we should ask ourselves the following questions: What does it mean that urban health food stores from South Africa to Berlin to New York and Canterbury sell these “wild fruits” marketed on a large scale? Will the fruit lose its local nutritional power as it is domesticated? It is possible that local landscapes will be destroyed, as has happened with the peat forests of Indonesia, in efforts to create more space for lucrative palm oil plantations. Will the edge-dwellers become plantation workers as a wild fruit becomes domesticated? Will baobab go the way of quinoa and goji berries and transition from a crucial supplement to an unobtainable luxury? Perhaps local residents will instead find ways to use baobab as a means to enter economic markets, as Walsh-Dilley (2013) has noted of Bolivian quinoa farmers. With the increased encroachment on local food practices by conservation legislation, what will happen to local people’s important nutritional sources?

When we purchase foods and buy into the trendy food marketing buzzwords, we need to be aware of the impact of our purchases. The superfood trend gives us yet another opportunity to critically engage with our purchasing practices. By critically engaging with the materials we consume, we can become better informed actors in the global network that is our planet.

Amber Abrams is a PhD candidate at the School of Anthropology and Conservation at the University of Kent in Canterbury, with partial support through a research scholarship at the University of Kent and the South African National Research Foundation. She works as a Senior Scientist at the South African Cochrane Centre at the South African Medical Research Council and has been involved as co-author on two Wellcome Trust International Engagement grants.

Please note: The links provided are one way of looking at an issue. My provision of these links should not be understood as agreement with or support for the content but simply as an example of related materials.

Notes

[1] While superfood marketers sell their products with claims that they have high doses of life-enhancing nutrients, in 1968 Jeliffe used the term “cultural superfoods” to describe items of sociological importance to localized food practices (Gurney 1975).

[2] Edge-dwelling is also implicated in increased challenges to food access, as three key elements of food deserts—increased fruit and vegetable prices, socioeconomic deprivation, and a lack of locally available supermarkets—are apparent in my research site (Pearson et al. 2005).

References

Anderson, D.G., and E. Berglund. 2003. Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Ballet, J., and A. Carimentrand. 2010. “When Fairtrade Increases Unfairness: The Case of Quinoa from Bolivia.” Working paper FREE – Cahier FREE no. 5.

Brockington, D., R. Duffy, and J. Igoe. 2008. Nature Unbound: Conservation, Capitalism and the Future of Protected Areas. London: Earthscan.

Chennels, R. 2003. “Case Study 9: South Africa – The Khomani San of South Africa.” In Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas in Africa: From Principles to Practice, ed. J. Nelson and L. Hossack. Moreton-in-Marsh, UK: Forest Peoples Programme.

George, S. 1998. “Preface.” In Privatizing Nature: Political Struggles for the Global Commons, ed. M. Goldman. London: Pluto Press.

Gurney, J.M. 1975. “Nutritional Considerations Concerning the Staple Foods of the English‐Speaking Caribbean.” Ecology of Food and Nutrition 4, no. 3: 171–175, DOI: 10.1080/03670244.1975.9990424

Jacobsen, S.E. 2011. “The Situation for Quinoa and Its Production in Southern Bolivia: From Economic Success to Environmental Disaster.” Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 197, no. 5: 390–399.

Osman, M.A. 2004. “Chemical and Nutrient Analysis of Baobab (Adansonia digitata): Fruit and Seed Protein Solubility.” Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 59: 29–33.

Pearson T., J. Russell, M.J. Campbell, and M.E. Barker. 2005. “Do ‘Food Deserts’ Influence Fruit and Vegetable Consumption? A Cross-Sectional Study. Appetite 45, no. 2: 195–197.

Walsh-Dilley, M. 2013. “Negotiating Hybridity in Highland Bolivia: Indigenous Moral Economy and the Expanding Market for Quinoa.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 40, no. 4.

Cite as: Abrams, Amber. 2016. “Superfoods: The Impacts of Marketing ‘Nutrient Powerhouses’ on Edge-Dwellers.” EnviroSociety, 4 May. www.envirosociety.org/2016/05/superfoods-the-impacts-of-marketing-nutrient-powerhouses-on-edge-dwellers.