I’ve been thinking a lot about superheroes and their worlds. This past term I taught a class, The Anthropology of Superheroes, where the big question posed was, “How can we study superheroes as anthropologists?” In addition to reading graphic novels and discussing cosplay and real-life superheroes, we also did collaborative event ethnography (Brosius and Campbell 2010) at the Alamo City Comic Con. I called it a swarm ethnography. I’ll admit, I’m a bit of a nerd and certainly a fan of the genre. However, what really interest me about superheroes are the imagined futures and alternative multiverses in which they live.

Superheroes are really a modern mythology, or supermythology, offering moral and sociological instruction and instilling a sense of awe in their target demographic. Through story, artistry, and imagination, comic books bring to life alternatives visions of our past, present, and future. They reflect our lived experience, even as they offer guidance into alternative assemblages of reality. Mythologies have long interested anthropologists, as they inform and reflect practices of different peoples. As Hirsch notes, “myths uniquely ‘assimilate’ events and processes into local performances and understandings of the world” (2006: 153), and these myths are not always pretty. But the comic book mythologies remain compelling and inherently hopeful. We know that the protagonists will prevail most of the time—that good will triumph over evil, even when the nature of what is good and what is evil are subjective and relative. While much of the action of these stories takes place in tension-filled urban spaces, I find these supermythologies to offer hopeful landscapes for the future.

For example, in the award-winning graphic novel Watchmen (1995), Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons offer contrasting landscapes of dystopia and utopia. The archetypal urban wasteland of a dilapidated New York City is contrasted with Mars (as well as the Arctic) as the heroes of the story seek to stop the imminent and seemingly inevitable annihilation of the human race through nuclear war. In this dystopic reimagining of the 1980s, Nixon remains president, the United States successfully defeated the North Vietnamese using the superpowers of Dr. Manhattan, but the tensions between the corrupt Nixon Administration and the Soviet Union remain high. Ultimately, in this alternative universe, made possible by the presence of superpowered individuals, our moral failings and abuses of national and international power are the sources of a decline. As described by the antihero, Rorschach, New York becomes the spatial representation of these moral failings. In his journal, he writes:

Dog Carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on the burst stomach. This City is afraid of me. I have seen its true face. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown. (Moore and Gibbons 1995: 9)

In Rorschach’s view, the city is “dying of rabies” (24), “an animal” (155), “reek[ing] of fornication and bad consciences” (22). Humanity has become a blight on the landscape; we are immoral and incapable of good. Driven by a Kantian sensibility of the virtuous and good will, Rorschach’s role is to rid the world of evil. He is a deontologist: virtuous, obligated to his moral code. But lacking any true superpowers, he is seemingly ineffectual against the decay.

By contrast, the only real superpowered character, Dr. Manhattan, is tricked into believing he is too dangerous for humanity and leaves for Mars. Created in a lab accident, where his intrinsic nature was torn apart, Dr. Manhattan forces himself back together, demonstrating his control over atomic and subatomic particles. As an omnipotent, near-godlike character, capable of manipulating time and space, his very “‘presence’ implicates ‘pastness’” (Munn 1992: 113) as he folds the space-time of his own existence. As a result, he exists simultaneously in multiple pasts, presents, and futures. On Mars, he creates a temple made from images of his own past, out of cogs and clockworks (he was destined to become a clockmaker before the nuclear age swept him into the sciences). Rhetorically, he asks, ”Who makes the world?” as he wills his own utopia into existence. Later, when confronted by his companion, Laurie (aka Silk Spectre), with the fact that the pending war will kill all of humanity, Dr. Manhattan despondently states from his Martian utopia:

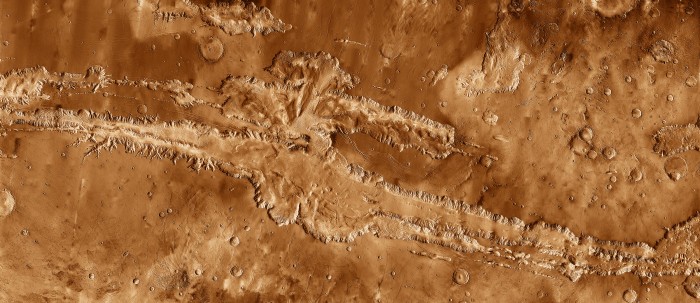

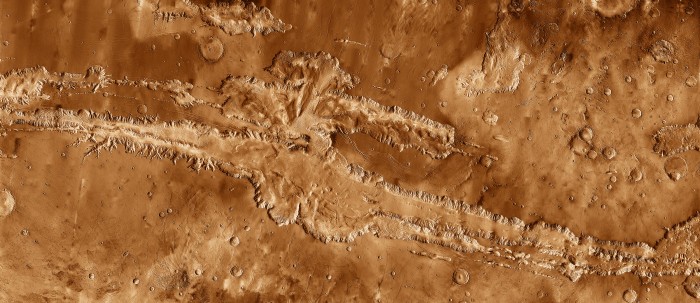

… and the universe will not even notice. We’ve been through this before, Laurie. You argued that human life was more significant than this excellent desolation, and I was not convinced. You attempted to compare the mere uncertainty in your existence with the chaos of the world [Mars] beneath us … But where are the pinnacles to rival this Olympus? Where are the depths to match those of… Ahh, but we near the Valles Marineris, you may see for yourself. (Moore and Gibbons 1995: 298)

Describing the Valles Marineris, he questions, “Does the human heart know a chasms so abysmal?” (299). Mars’s complex beauty is compelling for Dr. Manhattan, because of its absolute goodness. There is no evil, just geological and scientific processes playing out across the landscape—nature in a pure form, unencumbered by the blood-soaked streets and the moral failings of humanity. But then something happens. Dr. Manhattan’s perspective shifts, as he appreciates the complexity and miracle of human life displayed by Laurie. As the comic frames pan out from the Galle Crater, he proclaims, “We gaze continually at the world and it grows dull in our perceptions. Yet seen from another’s vantage point, as if new, it may still take the breath away” (307). The landscape of Mars smiles at us as we read. It is watching our earthly habitat with a sliver of hope in its eyes.

It is the view from beyond that superhero environments share with ethnography. Tensions remain between an idealized Martian landscape and the vermin-filled urban city, just as we contrast the apocalyptic dystopias of environmental destruction and the moral failings of global capital with our own idealized landscapes. Crapanzono reminds us that the view from beyond, from the imagined horizon of our own existence, is always “slippery” (2004: 21). In the realization of a dream, as we move forward, the horizon is moved—that the beyond is always just that. Watchmen ends with one of the heroes faking an alien invasion, killing hundreds of thousands, as a ruse to unite all of humanity behind a common cause. The hope for humanity is retained, but the hope for true superheroes moves just a bit further away.

—–

This past summer, I was in Papua New Guinea as part of my long-term research on mining labor, gardening practices, and the emergence of neoliberal subjectivities. I have been working in Morobe Province with Biangai speakers since 1998. While there in June, July, and August of 2015, I witnessed the initial onslaught of El Niño–driven drought. Massive grass fires from miles away filled the valley with smoke and debris, hiding the distant mountains, even on an otherwise clear day. A real dystopic nightmare seems possible from the back of my residence. Whether caused by human failings or natural variation didn’t matter; human life and well-being were at stake.

Fires were just one of the problems. By August 2015, my Biangai friends and family were becoming concerned about the impact of the heat and lack of rain on their gardens. We hadn’t seen real rain in months, and their gardens were starting to reflect this. Newly planted sweet potato vines were shriveling up, discouraging folks from planting more. One farmer complained that with the sun withering the vines, there was no ground cover. The direct sun onto the surface of the tropical soil was literally cooking the sweet potatoes before they could be harvested. He showed me with some amazement newly harvested crops that were already softened by the intense heat. Families were able to get by using money from the sale of this season’s coffee to buy rice. Those with employment purchased their staple crops from the market some three hours away. Dry season crops were also harvested at a quicker rate, relying more on heat-tolerant taro crops and by hunting animals that ventured into human gardens to find food and water.

Part of my research over the summer involved surveying each garden, mapping the location, noting the variety of crops planted, landownership, and the state of the garden. I’ve conducted this survey four times (2001, 2011, 2014, and 2015), and this year was startling because of the reduced emphasis on sweet potato gardens. Employment opportunities at the mine were only part of the answer, as many hesitated to invest the time given the impact the heat was having. As I surveyed each food garden, it became clear that the drought was going to impact food supplies for many months to come.

In contrast to earlier climatic events, the impact of this El Niño was seen as more severe and perhaps more life threatening. My host family and I talked about climate change, global warming, and what they will do if it does not rain soon. Having participated in a conservation effort between 1990 and 2005, they were well versed in the international discourse of environmental dystopia. Others recalled the impact that the last El Niño event had on coffee prices. With storms devastating the Brazilian market, global prices had increased during the 1997–1998 coffee seasons. They profited greatly. Thus, while the El Niño was never seen as a positive turn of events, Biangai sought to make the best of it.

But they too believe in superheroes of sorts. Or rather, they imagine hopeful alternative landscapes and realities. Many Biangai started to document crop losses, as they had during previous droughts. They planned to petition the government and the mining company for support. Royalties and employment from the gold mine were both seen from the perspective of a utopic mythology where an ancient ancestor had promised to provide them with resources for their future. While yams were originally said to be the ancestral gift to future generations, some astutely claimed that gold filled this role (Halvaksz 2006). The gold, as that ancestral gift, would see them through this latest climatic perturbation.

—-

What I learn from reading comics is that there is a place for hope in our imagined spaces. As I wrote this essay, a climate accord was reached in Paris at the UN Climate Change Conference. The Paris Agreement is like a supermythology, providing its audience with moral and sociological instruction and instilling a sense of awe in achieving the first global accord. It still exists in an alternative reality, requiring ratification by fifty-five nations and facing an already mounting critique from conservative parties and industries. Yet, like superhero narratives, it suggests the possibilities of a different future. The Watchmen, Biangai narratives about dealing with climate change and the El Niño, and the Paris Agreement all share a creative “friction” (Tsing 2004) that makes critical interventions possible. We need these supermythologies—not because they are real, but because they give us hope.

Jamon Halvaksz earned his PhD from the University of Minnesota and is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. In addition to being a comic nerd, he is also an environmental anthropologist, who is especially interested in locations of development and change where competing values of nature and resource management practices are at play. His long-term fieldwork among the Biangai of Papua New Guinea, for example, has focused on mining, conservation, and agricultural strategies. As a lifelong comic book reader, he recently developed a class that examines the role of superheroes in society.

References

Brosius, Pete, and Lisa Campbell. 2010. “Collaborative Event Ethnography: Conservation and Development Trade-offs at the Fourth World Conservation Congress.” Conservation and Society 8, no. 4: 245–255.

Crapanzono, Vincent. 2004. Imaginative Horizons: AnEessay in Literary-Philosophical Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Halvaksz, Jamon. 2006. “Cannibalistic Imaginaries: Mining the Natural and Social Body in Papua New Guinea.” The Contemporary Pacific: A Journal of Island Affairs 18, no. 2: 335–359.

Hirsch, Eric. 2006. “Landscape, Myth and Time.” Journal of Material Culture 11, no. 1/2: 151–165.

Moore, Alan (author), and Dave Gibbons (artist). 1995. Watchmen. New York: DC Comics.

Munn, Nancy. 1992. “The Cultural Anthropology to Time: A Critical Essay.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 93–123.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2004. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cite as: Halvaksz, Jamon. 2016. “Supermythologies and Superenvironments.” EnviroSociety. 11 January. www.envirosociety.org/2016/01/supermythologies-and-superenvironments.